Conclusion of a 2,500-kilometre off-road odyssey through B.C.’s remote backcountry

By Larry Pynn

British Columbia’s Chilcotin region is big country with larger-than-life characters, several of them authors. Paul St. Pierre wrote short stories about ranch life, Chris Czajkowski detailed one woman’s experiences alone in the wilderness, and Rich Hobson recounted the early days of cattle ranching.

As Murray Comley and I ride west from the Fraser Canyon into the Chilcotin, we seek yet another locally renowned figure, Chilco Choate. The retired big-game guide-outfitter described his life in three books, including one that explored his rocky relationship with the Gang Ranch.

At 81, Chilco lives alone at Gaspard Lake where someone set him up on a computer with satellite Internet. He sent me an email message weeks ago with directions to his place, but today they make about as much sense as a diamond hitch on a pack horse.

Murray resorts to his GPS and leads us along good gravel to a six-kilometre dirt backroad extending to Gaspard Lake. Murray’s 1995 BMW R1100G is equipped with knobby tires, but my loaner KTM 1190 Adventure is not. I’m also a short guy on a big bike unable to touch the ground without shifting my butt to one side of the seat.

“If it gets too rough you can always turn back,” Murray offers. Of course, once you are half way, you’re all the way in.

The road starts fine, a country ramble through scenic forests, but turns to slippery mud laced with deep ruts.

I adopt a bad approach to a puddle and dump the bike at slow speed. An even larger one looms ahead.

“You don’t have to do this,” Murray advises, ready to grab the bike from me.

“I’m afraid I do.”

I aim as straight as possible, but it makes no difference. Down I go, dipping my entire lower body in chocolate goo. Once the bike is righted again, I walk alongside it until we are on dry ground again and soldier on through improving conditions.

“You’re livin’ the life now, Larry,” Murray says with a smile.

“Yeah, your life.”

Fortunately, Gaspard Lake is not far beyond. Murray rides down to a gorgeous peninsula campsite where he chats with the owner of a pickup truck who came in the same away. Fallen trees punctured holes in his camper unit, so I guess I haven’t fared too badly.

We ride a short distance further and come to a property distinguished by log cabins and a sign: “There’s plenty of room for all God’s creatures. Right next to the mashed potatoes.” Methinks we are here.

I walk up to the door of one cabin and spot Chilco sitting on a well-worn chair looking into the distance. I shout and knock loudly, but it’s his dog that alerts him.

Chilco puts in his hearing aids, but they make little difference. We have to shout in his face and speak deliberately in case he can lip-read. The conversation becomes comedic.

I tell him my destination is a First Nations community at the end of the road, in the Rocky Mountain Trench.

“I’m headed for Fort Ware.”

“Where?”

“Fort Ware!”

No surprise when Chilco says he has radio-telephone access but doesn’t use it because he can’t hear what the other person is saying. “Everyone sounds like Donald Duck.”

Pouring us some dark rum, he explains that he sold his property some years ago under the condition he could live out his life here. There was so much snow two winters ago that he spent five months on his own.

Chilco says he bought the region’s first snowmobile, a Polaris Autoboggan, in 1964. “I had a theory about Polaris snow machines and bikes: ride a Polaris and walk home. Of course, they’ve improved since then.” He still uses a snowmobile to haul water in winter.

Chilco married and divorced twice, and recently rekindled relations with his first wife after 33 years. “In a sense, I’ve spent half my life by myself.”.

He pulls a book down from a shelf and signs it, simply, “Still here.” Then Murray and I continue north along the 2200 forestry road headed for Highway 20 — the Chilcotin’s main thoroughfare between Williams Lake and Bella Coola.

The landscape turns dramatic as the road descends steeply along switch backs to Farwell Canyon and B.C.’s largest sand dune at the Chilcotin River upstream of its confluence with the Fraser River. We cross a bridge and continue uphill through grasslands and gullies near 4,573-hectare Junction Sheep Range Provincial Park. At Highway 20, we head west to the relative luxury of Swiss-owned Kinikinik cabins and restaurant. “There’s something to be said for pavement after a while,” Murray allows. “Smooth and traction guaranteed.” Kinikinik is named after a local plant and, while expensive, looms like an oasis with its manicured green lawns.

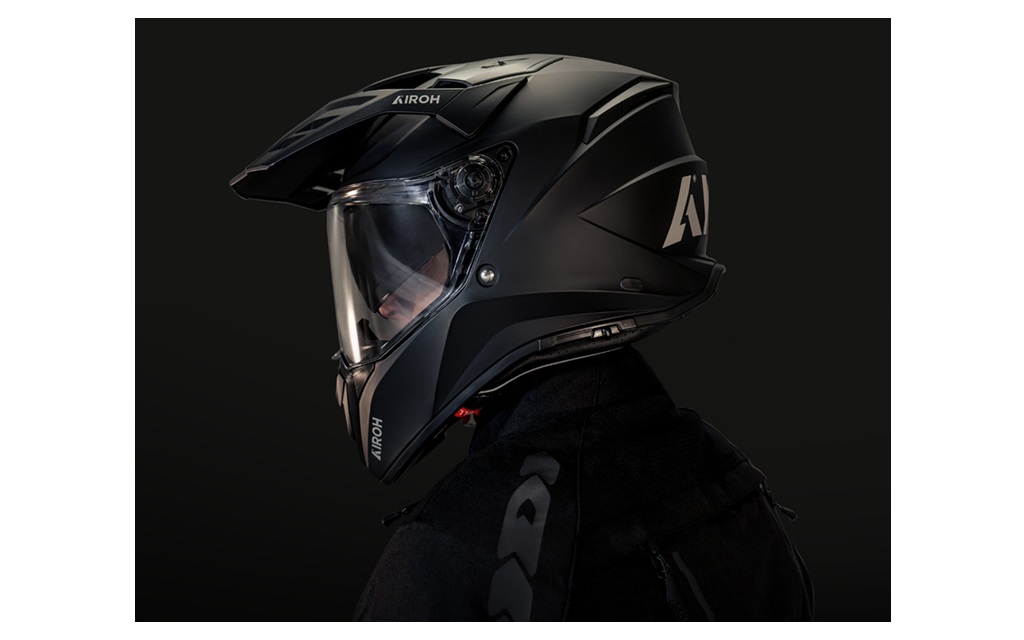

The next morning we meet Mario Pinto, a worker from the Kitimat smelter riding a 2015 KTM Adventure R — even taller than my bike, but with dual-sport tires. He is starved for conversation and quickly invites himself along on our expedition for a couple of days.

The adventure racer says the KTM is his 48th bike. He doesn’t like the fact the seat is heated and not the handlebar grips, and having to reset the traction control each time he starts the bike. He does loves the comfort, ergonomics, and power. “The fun factor is absolutely amazing. It’s very off-road oriented compared to almost every single motorcycle out there.”

My 230-kilogram Adventure tells me the tire pressure and mileage left on the tank, features stability control and anti-lock braking, and its 150 horses are indeed an adrenaline rush. The high-tech bike has probably saved my ass more times than I know.

The three of us ride west to Tatla Lake, then south on gravel again to the north end of Chilko Lake, the largest natural high-elevation lake in North America. It’s also grizzly country in fall when so many bears roam the shoreline for spawning salmon that officials recently closed the campground in the interest of public safety.

Bear Camp is a safari-style ecotourism resort featuring elevated wooden platforms that allow guests to safely view the bears below. A massage therapist is waiting in case you strain your neck. “The bears are completely comfortable eating salmon while you’re having coffee,” explains Ashley Scanlan, a partner in the business.

As the lake yields to the Chilko River, we cross a small bridge at Henry’s Crossing and ride south along a rutted four-wheel-drive route that roughly parallels the northeast side of Chilko Lake. The route is dry and passable and features dramatic stretches of old-growth Douglas fir adorned with lime-green moss.

This used to be provincial Crown land, but all that changed in 2014 when the Xeni Gwet’in (honey gwe-teen) First Nation received title to about 1,750 square kilometres in a landmark Supreme Court of Canada decision. For now, motorcyclists are permitted to access the band’s roads provided they show respect, obey campfire bans, and stay off sensitive grasslands.

That’s a friendlier scenario than 1864 — the so-called Chilcotin War — when natives killed 20 whites, mostly members of a road-building crew, resulting in the hangings of six chiefs.

Murray takes a wrong turn and we conveniently wind up at Tsuniah Lake Lodge where Vicki Brebner is barbecuing pork chops for her fly-in guests. “Most guests fish, but a lot come to just enjoy the peace and quiet.” For $35 apiece, we get a sumptuous dinner, topped with strawberry shortcake and whipped cream.

It is early evening by the time we reach the Nemiah Valley — an area so remote that the Xeni Gwet’in did not have road access until 1973. More than a dozen wild horses with flowing manes run powerfully across the road in front of me. Aboriginals regularly round up horses for their own uses, evidence of a horse culture that predates European contact.

A heavily rutted spur road leads to a lakeside campsite known as the movie camp. Locals got jobs as extras here during filming of the 1974 U.S. drama The Bears and I, co-starring Chief Dan George. Nearby is a replica pit house to give tourists insight into traditional lifestyles.

Chilko Lake’s predictable winds keep the mosquitoes at bay, and the glacially fed lake keeps the beer cold. The snow-dappled backdrop of the Coast Mountains completes an achingly perfect scenario.

The next morning we rise at 5:30 a.m. to get the jump on foreboding weather threatening to turn the dirt roads to gumbo, and continue on to Highway 20 at Hanceville rather than wait for the band’s service station to open. Murray runs out of gas twice, but Mario has spare bottles to help him limp to Lee’s Corner road stop. That’s where Mario resumes his own journey, and Murray and I continue east almost to the Fraser River then head north on Meldrum Creek Road.

Gravel leads to pavement — and other motorcyclists making the day trip from the mill town of Quesnel. It is a lovely ride featuring views of the Fraser River, wildflower meadows, farmlands, a cinnamon-phase black bear scooting across the road, 16 turkey vultures circling overhead, and a doe playing with its two fawns.

We return to gravel west of Quesnel and continue north through Blackwater River country and the trail used by the legendary North West Company explorer and fur trader Alexander Mackenzie in 1793 to reach the Pacific.

The promise of a home-cooked meal and comfortable beds awaits at historic Batnuni Ranch, once the realm of author and cattle rancher Rich Hobson and currently owned by Midge and Lock Downie. They are refugees from Chilliwack in B.C.’s bustling Fraser Valley who bought the 120-hectare ranch with trapline in 2008 and keep a Noah’s Ark of livestock, including sheep, pigs, goats, and chickens. Bats even roost around their shutters and under the eves. Eight years in, the ranch is up for sale again. “Lots of wildlife — we had wolves howling just a few nights ago — and peace and quiet, but too far out of town,” Midge concedes.

More gravel resource roads lead north to Highway 16 — the paved connector between Prince George and Prince Rupert — at the town of Vanderhoof.

This is where Murray, an industrial-supply salesman, heads west on business, and I continue north alone to historic Fort St. James on Stuart Lake. I fill up with gas one more time then proceed into deteriorating weather that turns exposed dirt patches on the road slick.

This is northern bush country — vast and unremarkable stretches of Crown forest ravaged by logging clearcuts. The first place of any consequence is Manson Creek, an 1870s gold-rush community where it is hard to distinguish between the historic properties and occupied homes.

I’m stopped on the main street considering my options when two modern-day placer miners on a quad drop by for a visit. One is very drunk and obnoxious. He kicks my rear tire and scoffs at the concept of venturing into this wild country with street tires. “You’re not with a motorcycle magazine,” he taunts. “You’re a fuckin’ axe murderer on the run.” In a quick turn of events, they actually sell me some gas before leaving on good terms.

I don’t take any chances. As the rain begins, I reorganize a wood shed to make room for my tent and leave an axe out front: “You want a piece of me?”

Weather conditions improve the next morning as I ride east on the Finlay-Manson forest service road and connect with the Finlay forest service road heading north.

Just before the Omineca River, I pull into a Conifex logging camp where contracted camp manager Evan Turcotte offers me lunch and a tour of the Williston Lake operations.

He, too, questions the wisdom of my journey. He once had three flats on his pickup truck driving from the resource town of Mackenzie to camp — 172 kilometres of gravel. “I wouldn’t drive here without a spare. Good God, no. You’re lucky you’ve got this far.”

Additionally, more than 100 logging trucks will flood the resource road tomorrow and they’ll be using radio channels I cannot monitor for ongoing traffic. “The amount of traffic for a motorcycle would be frightening as hell,” he continues. “Come back with a truck, a radio and some spares.”

Okay, I get it. The deteriorating weather, bleak landscape, and remaining 250 kilometres to Fort Ware further seal my decision to turn around and head to Mackenzie and home to Vancouver on pavement along Highway 97. Evan kindly tops up my gas tank, takes my photo next to a line of parked rigs and a load of logs, then wishes me luck on the return trip.

Dark storm clouds continue to swirl overhead, but the weather holds — as do the tires. Random shafts of light even make the clearcuts look good. I pass an abandoned pickup with a blown-out tire and an SUV with smashed out windows — not that I needed more convincing.

The KTM tells me I have travelled a total of 2,574 kilometres over 42 hours at an average speed of 61 kilometres per hour.

Those are the cold statistics. The reality is that despite the mismatched bike and lack of off-road experience, I have learned much and improved my motorcycle skills immeasurably on this backroads adventure of a lifetime. This is not the end of a journey, it’s just the beginning.