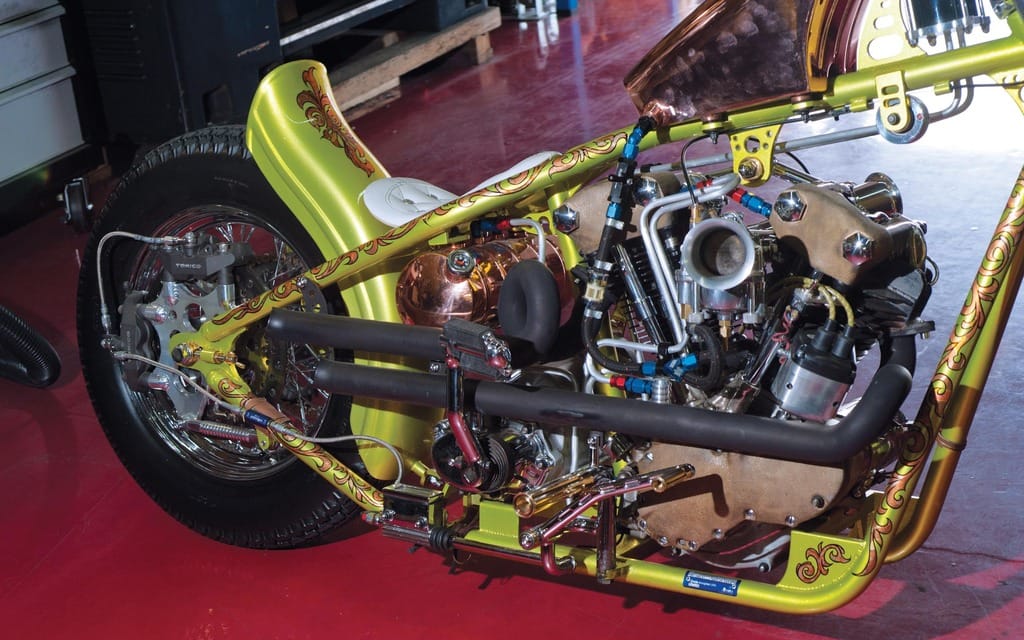

The Unicorn is Down –

But Not Out as Mad Jap and Jesus Imposter Resurrect a Mythical Chopper

Jesus stands next to a unicorn. No, seriously. He does. And he has a sword. With which he is stabbing the unicorn. And of course there’s a rainbow.

Dale Yamada of Mad Jap Kustoms dreamed up the image, and knew it would look good airbrushed onto his new chopper. So he talked to Calgary artist Doug Veness about it, and Veness suggested the unicorn should bleed Skittles. Oh, no, Yamada said — let’s not strain credibility.

Skittles are out, then, but painted a bright white, the Unicorn chopper is still pretty tasty. It’s an anti-image bike — Yamada’s Gabriel to everybody else’s Lucifer. But it turns out that Jesus, or at least someone who resembles his popular image, did in fact slay the Unicorn. Leo Tancreti wears long, unkempt hair and a full beard, and runs Leo’s Speed Shop in North Haven, Connecticut. Yamada flew him to Calgary to help prepare a machine for the upcoming Born Free 4 custom bike show in Los Angeles. Then, while taking a ride on the Unicorn, Tancreti pushed it a little too hard and discovered the bike’s limitations.

“I was more concerned about Leo than the bike,” Yamada says. “Bikes can be fixed.” Tancreti was scratched, but not seriously injured. “Leo killed the Unicorn!” Yamada posted on Facebook.

Quickly the Unicorn will be resurrected. Tancreti soon had the bike apart, with the frame to paint and alloy polished and sissy bar tweaked and sent for chrome plating together with the exhaust. It could be a miracle, but the airbrushed artwork on the hand-formed gas tank suffered no damage. “It’ll be done by Tuesday,” Yamada said. Which is good, because one of his greatest joys is closing shop, kick-starting the Unicorn, and riding. He’ll take three or four days and travel south to Montana, or west into the Rocky Mountains and B.C.’s interior.

Yamada stuffs only essentials in a backpack, and bungie cords two 2-litre cola bottles filled with gasoline and wrapped in a blanket to the sissy bar. At 90 km to a tank, he wouldn’t otherwise have enough fuel for Rogers Pass.

“I ride the shit out of them,” Yamada says of his customs. “And I often end up riding by myself. I usually can’t find anybody who wants to share the same experience. Everybody wants to jump on their brand new bike, and they think they’re going for adventure. But they want to have everything planned out — where we’re going for this day, what we’re going to do, what we’re going to see. I don’t care, I just want to go. The whole point is not knowing what’s ahead, and just experiencing it as you go.

“My best rides are the ones when I have the most trouble. When I break down, or the weather’s shitty.”

Yamada likes the thought of simpler times, hippies and their easy sense of freedom. “It’s all these gay clichés,” he says. “I wasn’t around in that period, but I’d like to think it’s similar to what I do when I jump on the bike and just ride.”

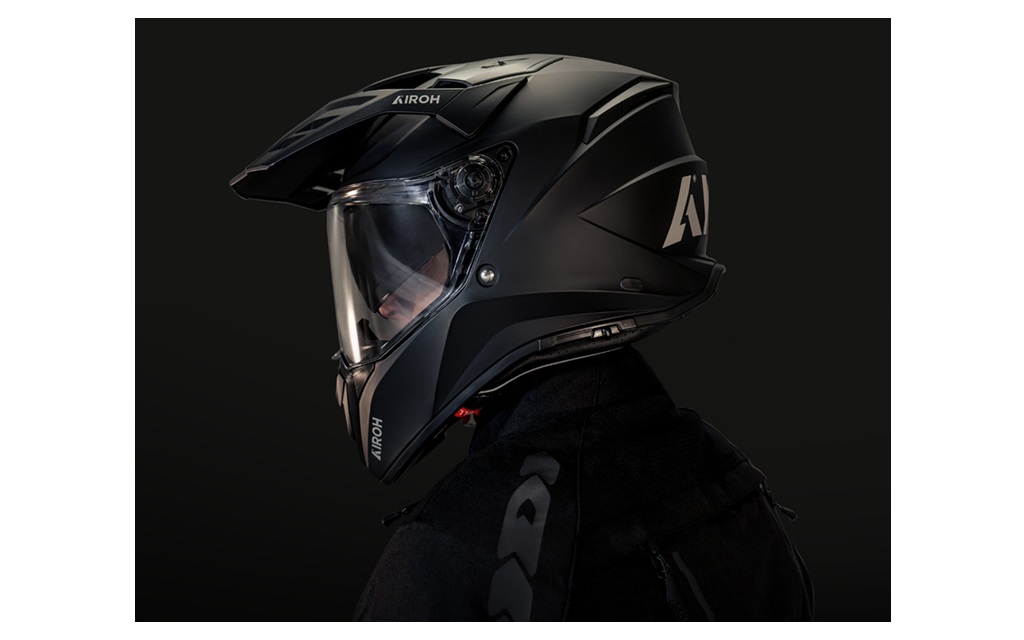

Born in Nanaimo and raised in the Vancouver area, Yamada grew up around custom Harley-Davidson motorcycles. These were machines of the 1970s, and his current builds are echoes of his youth. Yamada was managing a brake and muffler repair shop in 1996, though, when he bought his first bike, a used Suzuki GSX-R750. “I bought a helmet and all my gear at the same time I bought the bike,” Yamada says. “I rode it out of the dealership with all of the price tags still on my stuff. I was so severely hooked. I said this is my life.”

He’d raced BMX and mountain bikes and toyed with cars and 4x4s. But motorcycles had now lit his fuse. “At the first set of lights after riding out of the dealership, a guy on a red Honda CBR900RR nodded at me and said ‘nice bike.’ When the light turned green he took off and did a stand-up wheelie.” Impressed, Yamada learned to pull the same stunt.

“I started learning at the next light,” he laughs. Yamada rode hard on the street, and crashed often. He admits he was out of control when a local mechanic told him to get off the street and onto a track. A 1996 Suzuki GSXR 750, headlight taped and signal lights removed, was his first race bike, which he rode in Portland, Oregon. “I remember being nervous, and I’d crashed during practice,” Yamada says of his “beginner’s” race. “And my friends were there telling me to stop looking down — look ahead; that’s how green I was.” Yet, with 40 other racers, Yamada lapped the field and finished first. “I just pinned it and passed everything I could.”

Yamada did well as a privateer, participating in club events. In 1997 Race City Motorsport Park in Calgary lured him and his wife, Michelle, to the city. His life was working and racing, until 2004 when there was pressure to move up to the Nationals. He couldn’t make it happen, with a young family and a new hot-shot trucking service to operate.

Then, in 2007, he decided to build a custom motorcycle. Although an accomplished mechanic and tuner, Yamada had never constructed a one-off machine. He loosely based his first build on the choppers of his youth: Frisco tank, metal flake paint and chrome.

Just like that, he was in business, filling his garage with TIG welding equipment and milling gear. “I’m not a welder, I’m not a machinist, and I’m not a painter, but I do most everything for myself,” he says. He chose his late father’s nickname for his fledgling chopper shop: the Mad Jap.

More than one custom V-twin had rolled out of his garage, and deposits had been paid on at least six more when, in 2008, Yamada tangled with a car. “I remember the hit, how I flew, everything,” Yamada says. “I remember hearing the fire truck and the ambulance coming, and seeing all of the feet and people around me. And I remember seeing the damage to myself. I’d never felt pain like that before in my life.”

Yamada broke his pelvis in four places, his lower vertebrae (L 5 and 6), and there were multiple compound fractures to his left tibia and fibula. He also suffered serious internal injuries. Doctors told him he was going to lose his lower leg, but he fought to keep it. After he got home, Yamada was in a rough spot, and he was angry. He’d had to return the deposits, and the economy had tanked. Parts were in his stockpile, though, and the only thing Yamada could do was build.

Working from a wheelchair while his leg healed, Yamada crafted two customs, Funkmaster, and Sweet and Sour. He relied on friends to install engines and lift heavy components, and eight months later he was finished. Upon completion, Yamada sold Sweet and Sour to Sean Senos. “That lifted my spirits, and I said, ‘Okay, I can still do this.’ Sean has absolutely no idea what that did for me.”

Four years later, Yamada is in constant pain but he’s got his leg. It’s a little shorter than his right, and he can’t properly shift a motorcycle — he can push down on the lever, but he can’t pull up. That’s why every scooter he builds for himself is equipped with a jockey shift.

This spring, Mad Jap Kustoms moved to a single bay in a northeast Calgary industrial park. Yamada doesn’t miss working from home, and he feels more energized in the new space, even with distractions. “People come by and hang out, and because I live, eat, sleep, and breath motorcycles, they’re all welcome,” he said. “I’ve got guys on sportbikes and bone-stock cruisers stopping in.”

On the benches out back are Harley-Davidson projects. Most are customer bikes, handed over to Yamada for customization. There’s a stock Sportster on one lift. He is crafting mid-controls and installing a belt drive. “I don’t care what kind of bike I’m working on,” says Yamada, pointing to the Sportster, “but I do want someone looking at it to say, ‘Where’d you get those cool mid-controls?’”

In custom builds, Yamada says, the engine is the heart of the project.. He works around fully rebuilt Knuckleheads or Shovelheads. Recently, a customer rolled in a derelict Shovel chopper. Built in the late 1970s or early 1980s, it had no redeaming features that Yamada could see, and he convinced the owner to yank the motor. They’d start fresh.

There are other bikes in for repairs, ones that don’t look anything like the customs he appreciates building and riding. “In the end, who am I to judge what you ride?” Yamada said. “It’s about bikes in general. I really don’t care if it’s about building a full custom, fixing a tire, or changing oil, it’s a bike.”