*This article was published in Vol. 51 No. 5 of Cycle Canada digital magazine.

In the beginning, there was the KLX250. This quarter-litre dual sport was in Kawasaki’s lineup for 15 years, on and off. It saw a few updates, but Kawasaki kept it in the 250 class, even as the quarter-litre streetbike class grew from 250 to 300 to 400. It seemed like Kawasaki was happy to upgrade the KLX with fuel injection, but that was it.

Then, in late 2019, we got news of the new budget-oriented, learner-friendly KXL230 dual sport. Why have a 230 and a 250 in the lineup at the same time? Easy–a few days later, Kawasaki announced the KLX300R trail bike model. And then, in fall of 2020, Kawasaki said the KLX250 dual sport was discontinued, in favour of a KLX300 dual sport. The incoming and outgoing models are obviously related, but the 300 duallie is a new design, based on the KLX300R dirt bike.

Motor work

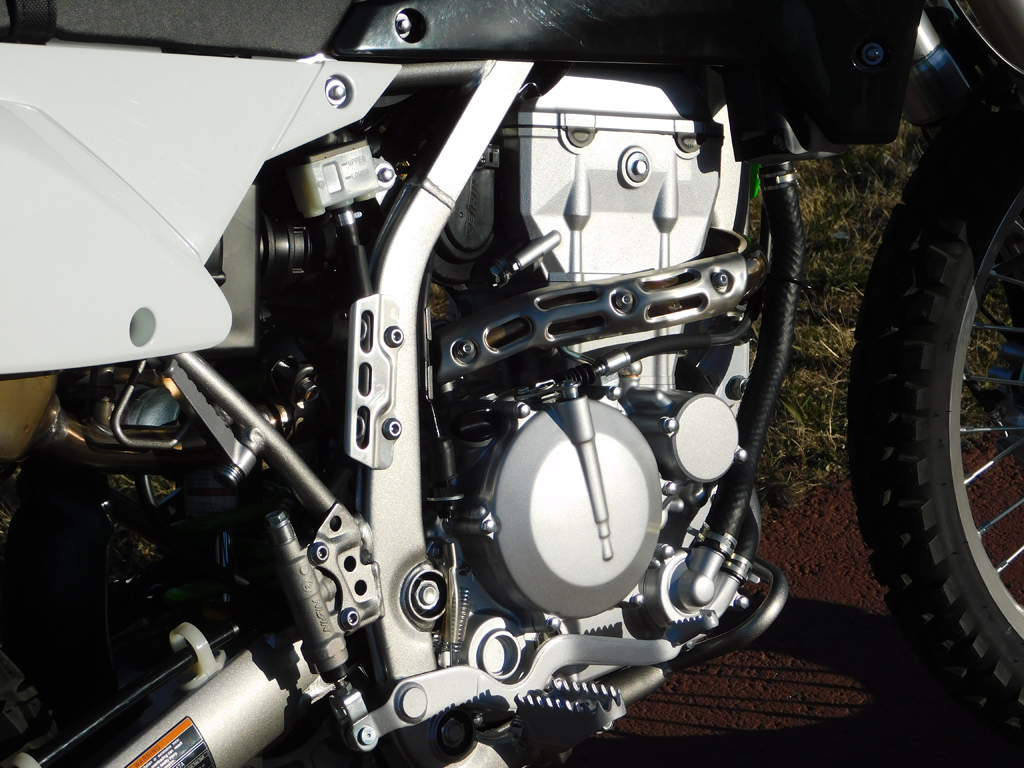

The big news here is obviously the bigger engine, which gets new cam profiles and higher 11:1:1 compression ratio as well. Thanks to a 6 mm larger bore, Kawasaki actually boosted the KLX250 to 292 cc, not a true 300. That’s close enough for most buyers, though.

Aside from those tweaks, the new engine isn’t that much different from the older liquid-cooled single-cylinder; it still has a six-speed gearbox, four-valve head, wet clutch, EFI, and so on. This is an evolution of an older design, and it’s not too far outside the box.

Kawasaki says the new engine makes more torque and horsepower than the old 250, everywhere in the rev range. While Kawasaki doesn’t hand out torque and horsepower numbers, best guesses have engine output at 29 horsepower at the crank. Unfortunately, I was not able to put the bike on a dyno and see the results at the rear wheel myself.

However, judging by the ol’ seat-of-the-pants dyno, the KLX’s engine work was indeed a welcome upgrade. I’ve ridden a wide range of quarter-litre dual sports over the years, ranging from weedy Chinese 200s to hairy-chested Euro 250s. Each engine has its own strengths and weaknesses. The reassuring chuffle of a low-performance air-cooled engine mutters that it’ll run forever, as long as you remember to check the oil and keep the revs down. The snarl of a high-strung offroad race-bike-with-lights promises plenty of wheelies and other offroad fun, at the expense of reliability. Generally, machines in this 200-250 range are plodders, or perky, but not both.

The KLX doesn’t get there either, but it offers a decent compromise between trail antics and street practicality. Off the line, it’s got noticeably more torque than the generally wimpy Japanese 250s. It’s not a wheelie monster, but it’s also not terribly hard to loft the front end.

On the street, the KLX300 has all the jam you need for around-town riding; indeed, one could argue the power is practically perfect for inter-city commuting. It’s easy to get to municipal speed limits, and it’s easy to stay there.

Once you leave the city, the KLX300 is equally suited for backroad blasting. You can ride this thumper all day long on two-laners with speed limits in the 80-90 km/h range, without wearing yourself or the bike out. It’s got just enough zip that you can have fun in the corners and you won’t lose too much speed in rolling hills. For most of the time I had the bike, I explored New Brunswick’s bumpy byways and two-track gravel, and the KLX was perfect for this.

Out on the four-lane highway, the KLX300 is still a bit light on horsepower and torque. You can keep up with the 100 km/h traffic, even the 110 km/h traffic, but it’s not fun, especially when you get to long grades. It has more highway capability than most of the old 250 class, although a lighter rider who borrowed my Yamaha WR250R easily pulled away from me, when we rode side-by-side on the highway (note to self: time to lose some weight, again).

Overall, I think the updated KLX engine is a good compromise; if I was using this as a travel bike for something like the Trans Labrador Highway, I’d pack a larger front sprocket, to swap in for the extended asphalt stretches. If I was using it mostly offroad, I’d be tempted to go to a slightly larger rear sprocket (stock gearing is 14-40), for improved offroad capability. As it sits, it’s just about in the middle, where it needs to be.

It’s too bad Kawasaki didn’t get rid of some of the high-revs buzz, but that’s life with a thumper, and you can’t really complain about that. The only real issue I had with the engine was, my bike lacked Kawasaki’s usual slick-shifting gearbox. It’s highly likely this was because the KLX wasn’t fully broken-in. I suspect the annoying missed first-to-second shift issue (caught in neutral, something that never happens with Kawis) would disappear with the next oil change. Or maybe I’d start paying more attention to my shifting?

Classy chassis

Kawasaki says the KLX300 is based on the KLX300R chassis. Visually, it appears to be pretty much the same as the KLX250 frame, but the specs indicate there are indeed some differences. It sits lower to the ground (275 mm ground clearance), and seat height is slightly higher (895 mm).

Like the 250, the new 300 has compression-adjustable forks (255 mm travel) and rebound- and compression-adjustable shock (230 mm travel). The suspension is soft when compared to thoroughbred Euro enduros, but superior to any other Japanese bike I’ve ridden in this class. It works for both street and trail, and the adjustability (not always available in the smaller-cc Japanese bikes) means you’ve got basic tuning capability.

I was particularly happy with the rear end’s hook-up in the dirt. Over the years, I’ve had several Japanese duallies in the 200-650 range that would bounce the rear end all over when pressed on an unpaved road or trail. The KLX was composed, not topsy-turvy as soon as it hit some whoops. Again, the suspension is very much a compromise, but it’s better-tuned than previous el cheapo 250-class machines.

Braking is unremarkable, not noticeably good or bad. For 2021, ABS is unavailable for the KLX300, sadly (still available on the KLX230, though). There’s a single disc up front, with two-piston caliper, and a single disc in rear, as is the standard these days.

Kawasaki says curb weight is 137 kilos; heavy by dirt bike standards, but slightly less than the old KLX250 model, and very much in line with current Japanese entry-level dual sports. Junk the hideous rear mudguard, and you can trim some of that weight off … which you’ll quickly regain, as soon as you bolt on handguards, a skid plate and maybe a larger fuel tank.

The bare necessities

The reality is, Kawasaki ships this bike in a very stripped-down form. A decade back, when you bought a dual sport, it came with floppy plastic handguards, and a chintzy plastic skid plate to match, offering minimal protection for casual users. The KLX300 doesn’t even come with those bits. If you plan on offroading anything more than the easiest of gravel roads, you should plan on spending at least $250 on farkles. Otherwise, you run the risk of smashing a hole in the bottom of your engine case, or breaking your levers (or worse, your hands). If you’re riding the trails, you’d be foolish not to buy these parts.

If you’re only riding close to home, the small 7.7-litre gas tank will be OK, but most riders will get tired of the Low Fuel light blinking at 120ish kilometres, and think about upgrading. A Kolpin can or bigger tank will mean the bike’s less nimble on the trail, but another gallon of gas would greatly improve your range. The KLX gets roughly 100 klicks for every five litres burned, depending on how hard you’re riding, so a 12-litre tank should take the rider well over 200 kilometres. By then, most riders are happy to get off a single-cylinder bike for a break anyway. In its current form, the Low Fuel light usually comes on around the 120-kilometre mark. It’s best to plan your gas stops accordingly; you can only push your luck so far, before you end up pushing your bike. Run out of fuel in the woods in black fly season, out of cell range, and you’ll probably not make the same mistake again.

The bottom line

The KLX300 is a better basic dual sport. It doesn’t have the grunt of a 350, and certainly not the grunt of a 650. Unfortunately, it does have the price tag of a 650.

However, with supply chain issues, there probably won’t be a 650 for everyone who wants one in 2021. And, some riders just don’t want a 650; they’d prefer the KLX for its offroad-friendly weight and handling, as it certainly beats the DR650 offroad in stock form, and probably the new KLR as well. And, the KLX is a decent improvement over older Japanese 250 singles. And, whether or not riders like it–prices are going up.

With that in mind, I think the new KLX300 makes good sense for a rider who wants a sturdy machine for combined on-road and offroad duty. Just make sure, when you’re planning your purchase, that you leave some room in the budget for a few farkles.