MV Agusta race bikes survive six decades in original owner’s hands

Suppose you were a budding privateer road racer in the mid-1950s and looking for your next ride. Easy: why not just write to the imperious Count Corrado Agusta in Italy and ask to buy two works replicas of his company’s first world-championship-winning motorcycle? Of course he would say no. But what if you wrote to him again and he said yes?

Brothers Len and Neil Tinker from Warrnambool, Australia, were the two lucky privateers in this unique and happy position. Slight of stature but strong and fit from years of manual labour, they were ideally suited to compete in the 125 and 250 cc classes of the Continental Circus.

The normal career path for Commonwealth riders usually led to a British 350 or 500 cc production racer but the Tinkers took a different tack. Being smaller of build and having pockets full of cash meant they could afford a pair of jewel-like MV Agusta single-cylinder grand prix bikes, each of which cost more than half again as much as a Manx Norton. They had caught Count Agusta at the right moment.

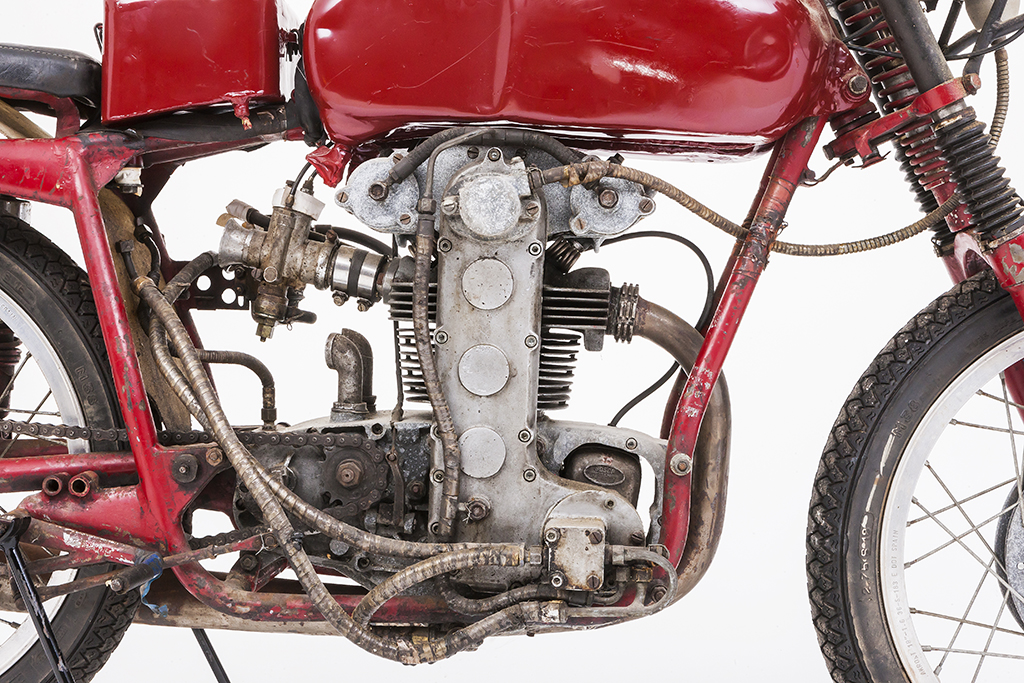

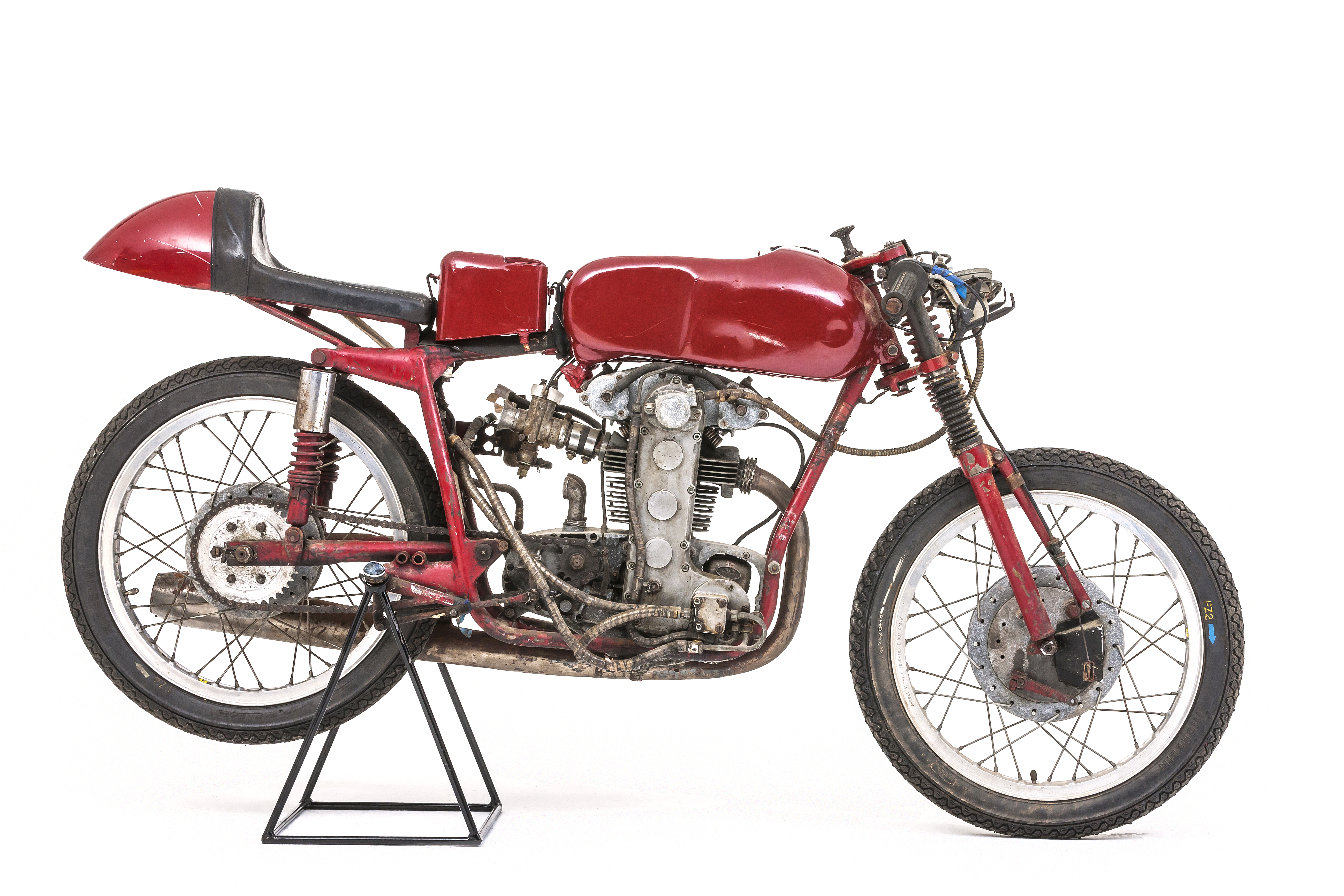

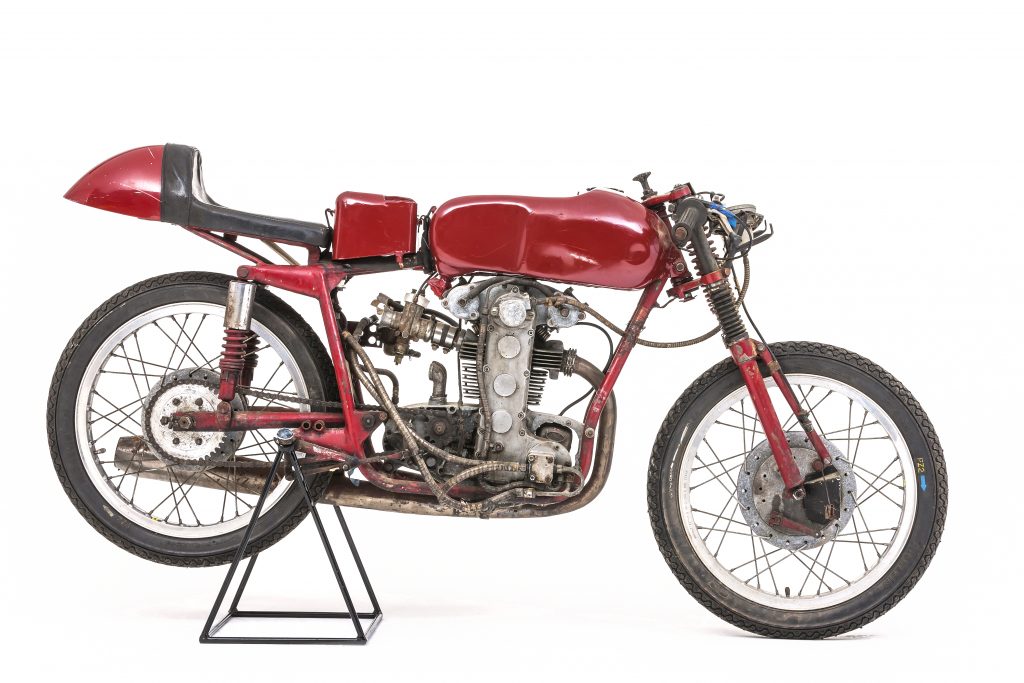

They duly placed an order for a 125 Bialbero (twin cam) of the type raced to a world championship in 1952 by Cecil Sandford and from 1955 onward by Carlo Ubbiali, plus a special 203 cc version that was within the limit to be eligible for the 250 cc class. The 125 was available in limited numbers to the public but the 203 was a works-only model. Neil Tinker explains that theirs was the only 203 supplied to anyone outside of the factory team. Ubbiali was 250 world champion for MV Agusta in 1956, Tarquinio Provini in 1958 with Ubbiali winner again in 1959 and ’60. Created in-house by engineer Piero Remor and first raced in 1950, the Bialbero was a highly successful design.

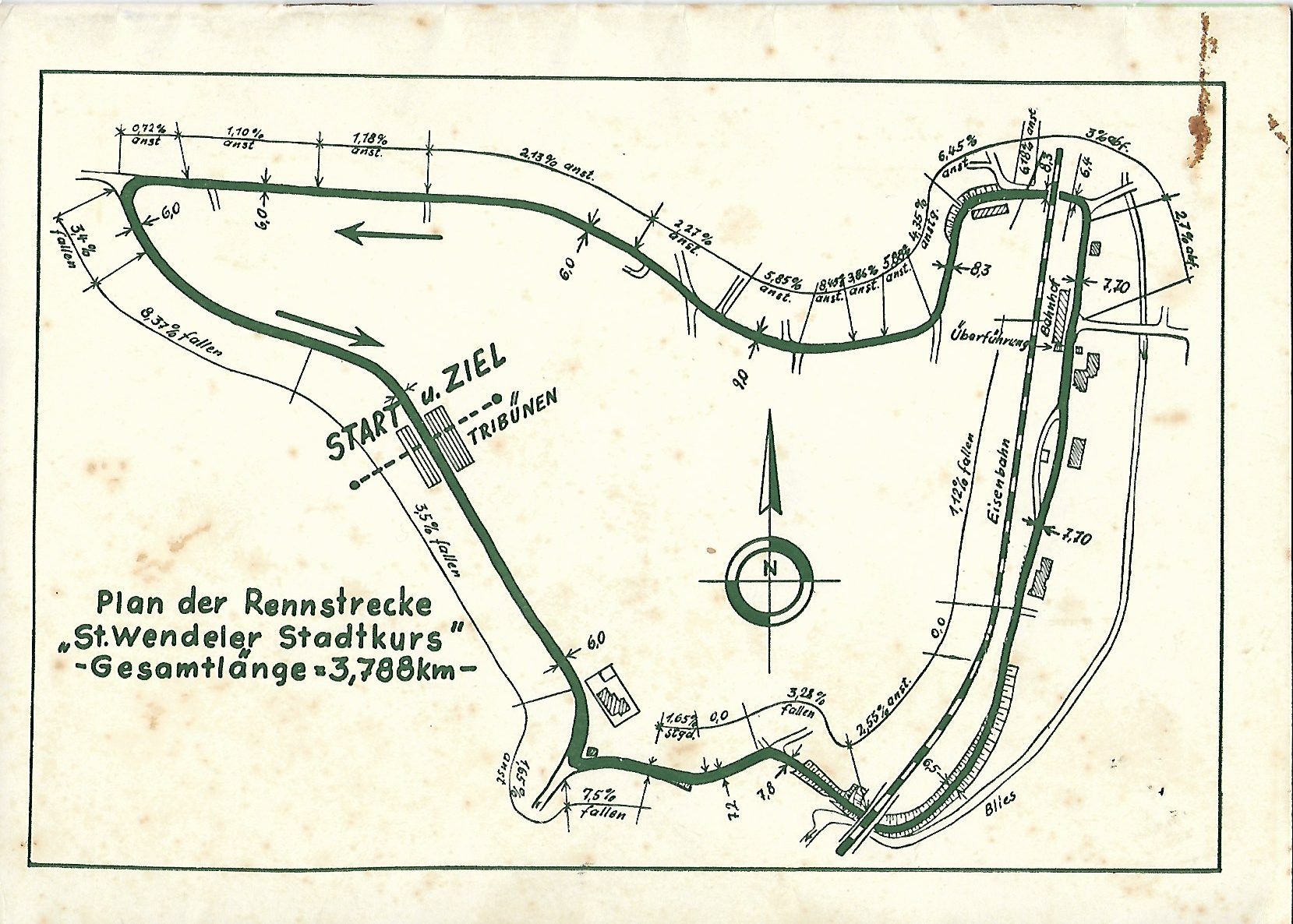

In due course the brothers received word that their bikes were ready. After the obligatory wine-lubricated two-hour lunch at the factory, they trailered their treasures to Germany behind a friend’s VW coupe.

As fate would have it, they enjoyed two challenging seasons of international and grand prix racing as its golden era was unfolding. A well-patinated pair of tiny MVs remains in Neil Tinker’s possession to this day.

Nor were they strangers to the MV Agusta marque even then.

Neil Tinker, the surviving brother and still sprightly at age 87, takes up the tale. “Len was three years older than me and we had lots of work in the late ’40s. Len wasn’t a scholar and he quit school at 14 to become a plasterer. I earned a diploma at tech school and became a carpenter, and we worked for the same firm. Len was always involved in racing and I tagged along. He and his pal Neil Henderson bought a 250 cc BSA B30 from about 1934–35 to race and we’d take it to a scrambles track about 12 miles away in a collapsed volcano called Tower Hill. Someone had a bulldozer and made a track about a mile long.

“Len bought a copy of Phil Irving’s book Tuning for Speed and read it cover to cover. He modified the old BSA and we used it for both scrambles and road racing. Ballarat and Fishermen’s Bend were the two main road races in Victoria. Harry Hinton (Sr.) usually won the 500 class.

“We knew we wanted to go to England. There was a whole cadre of Aussies who went. Len and Neil (Henderson) booked passage in 1952. I was booked to go in 1953 but then there was a coronation on and they cancelled all the bookings. You could rebook your ticket but they’d doubled the fare, so I didn’t get to go that year. I had to wait until ’54.”

Len Tinker wasted no time when he reached British soil. He was hired by BSA in 1952 to work at the factory in Birmingham on development of the A10 twins under engineer Cyril Halliburn. Len was involved in BSA’s Daytona project that culminated in 1954 with a sweep of the first five places on the beach with a mixture of Gold Star singles and A7 twins. At the Isle of Man in 1953 he hooked up with the two Keiths from Australia, Keith Campbell and Keith Bryen, and became their helper and fixer on the hard road across Europe during the summer racing season. Races were long and gruelling, and if it wasn’t the motorcycles in need of maintenance and repair it was the well-used transport van.

Away from Hitler’s autobahns, road travel was slow and primitive, and racing crews lived a threadbare existence. In the book Circus Life, Neil Tinker told author Don Cox, “Meals on the road consisted of rye bread, cheese and meatwurst sausage, and mugs of instant coffee. We would stock up with cans of instant coffee in England because it could be traded for cash or goods, especially in the Communist countries.”

He’d had the most enjoyment while racing behind the Iron Curtain, Neil said recently. Enormous spectator crowds in East Germany and Czechoslovakia made the most impoverished western rider feel like a celebrity. Start money was paid half in sterling and half in the local currency; what they didn’t spend in the country was wasted since it was non-negotiable elsewhere. “When going to East Germany we would buy stuff to leave behind. Hinton took enough parts to build a complete Norton over two years.” They could count on trading for things like advanced East German cameras and lenses in exchange.

Watching every penny, riders took advantage of the free fuel offered to competitors. They would top up the tank on their bike for every practice session and race, then empty what remained into a drum carried in the van to get them to the next race in another country a week or two away. Fortunately, petrol was the common fuel for the English-built Morris or Austin commercial van of the day.

In 1954 Len bought a single-cam MV Agusta 125 from German rider Hubert Luttenberger, who had earlier been a works rider for NSU. Luttenberger went on to ride for Adler and FB-Mondial and in 1958 won the German 125 cc championship.

Len competed on the MV in a couple of international races and placed second in Tubbergen, Netherlands, but the brothers decided it was not fast enough to gain a start in grand prix events. Something quicker was needed but money was in short supply. They’d heard about a massive defence construction project unfolding in the Canadian Arctic that paid high wages and with his training as a carpenter, Neil applied for a job and was hired. Len was seconded by BSA to act as a works mechanic for six special Gold Stars that had been prepared in the engine test department for the U.S. market. Passing through Daytona, he ended up working out of the BSA dealership in Pasadena, California.

Neil spent a brutally cold 10 months working in the far north of Canada on the Distant Early Warning or DEW Line building a network of radar stations that spanned 10,000 km across the Arctic to warn of a possible Russian bomber attack. The U.S.-funded project was a leviathan effort that employed 25,000 workers and brought in nearly a half-million tons of material and supplies between 1954 and its completion in 1957. Neil ended his contract back in Toronto in March 1956 with $4,500 in his pocket, equivalent to more than $41,000 today. A Manx Norton then cost $850.

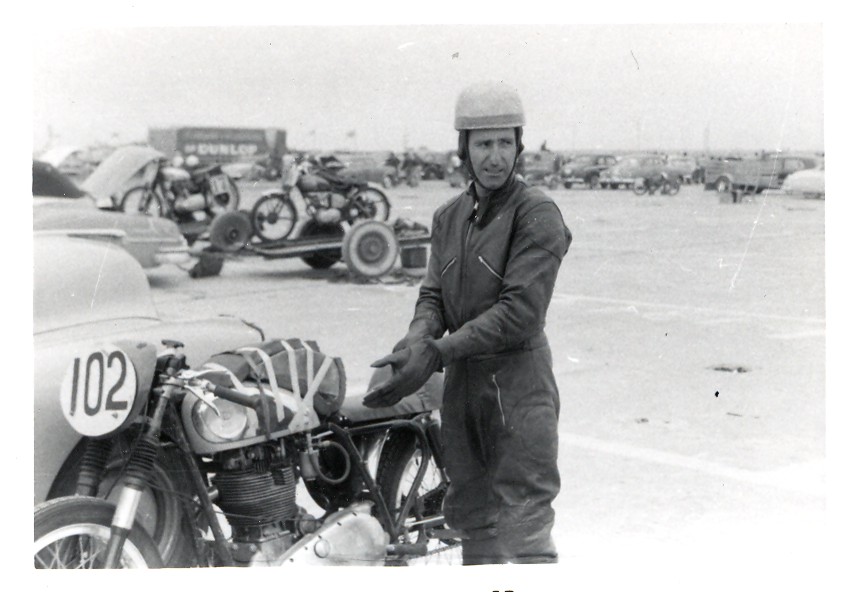

Neil flew to California to join his brother for the long drive back to Canada in Len’s Pontiac station wagon. They towed a trailer carrying the single-cam MV as well as a Gold Star that Len had assembled around a self-tuned engine he had built while working at the BSA race shop in Birmingham. In the summer of 1956 they raced in eastern Canada and earned enough points with the Canadian Motorcycle Association to qualify for FIM international licences. They sold the two bikes in Canada and returned to England in preparation for a renewed effort in Continental grands prix.

The Tinkers sized up the competition and decided to focus on the 125 and 250 cc classes. Competition was less intense and anyway, the 26-year-old Neil weighed a mere 98 pounds and big brother Len was only 108 pounds. Even in his full racing kit Neil had to carry ballast to meet the FIM minimum rider weight of 50 kg. The Australian brothers stood out from their peers by wearing American jet-style Bell helmets in an era when everyone else was in a pudding basin. Occasionally that put them offside with race organizers’ regulations and they had to switch.

In December 1956 Len wrote to Count Corrado Agusta requesting a twin-cam 125 and an ex-works 203. Agusta refused that request but after another pleading letter from Len he did offer to build a 125 and a new 203 to order. By then the factory had a full 250 cc twin-cylinder race bike under development. “They said our new bikes would be ready at the end of January, then it would be February and finally we picked them up in April. Hubert Luttenberger drove us to Italy because his car had a trailer hitch. I ended up wedged in the back seat of his VW Karmann Ghia.” The bikes cost $1,320 apiece.

Hubert also agreed to sell them another MV 125, this one a double-knocker that he had campaigned in 1956, “giving us two starts in the 125 class and one in the 250 class with the 203. The start money for the smaller classes was much less than the 350 or 500 classes so we needed the extra start to survive — to buy cheese and rye bread!”

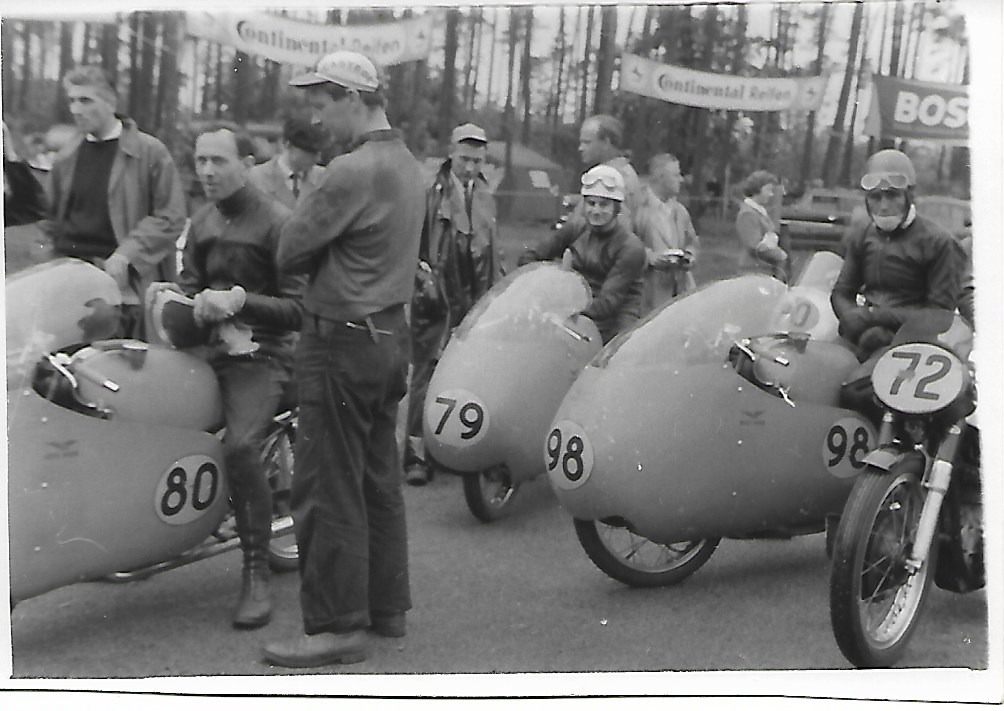

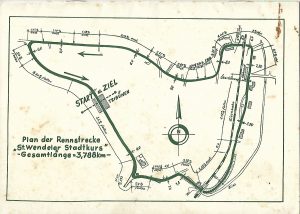

They spent three weeks back at Hubert’s home in a village near Kaiserslautern, where his mother fed them far better than they were used to. Hubert’s father had a machine shop where they could fabricate mounts for the dustbin fairings that Len had designed with the help of an aeronautical engineer and moulded in fibreglass using techniques he had learned while in California. Letters of application were mailed to race organizers across Europe; some accepted, some declined, some accepted provisionally depending on the brothers’ results in early season races. Getting on to the grid was a struggle and you had to prove your worth.

Neil generally rode and maintained the new 125 and Len the 203 plus the “old” 125, depending on the classes for which they’d been accepted or who was still recovering from an injury. Neither had a monopoly on occasional errors, running three finicky machines with no outside assistance. Both brothers experienced costly lapses, such as when Neil’s exhaust pipe dropped off at Spa-Francorchamps when he forgot to safety wire the nut, or when Len went off the track on the 203 at Hedemora in Sweden when the drain plug fell out of the oil tank for the same reason. Traction was a problem; a tire contract with Dunlop limited them to harder rubber when Avon or Barum could have offered a stickier alternative. Vibration was another plague with the high-revving singles, and they often had to get fractured components welded back together.

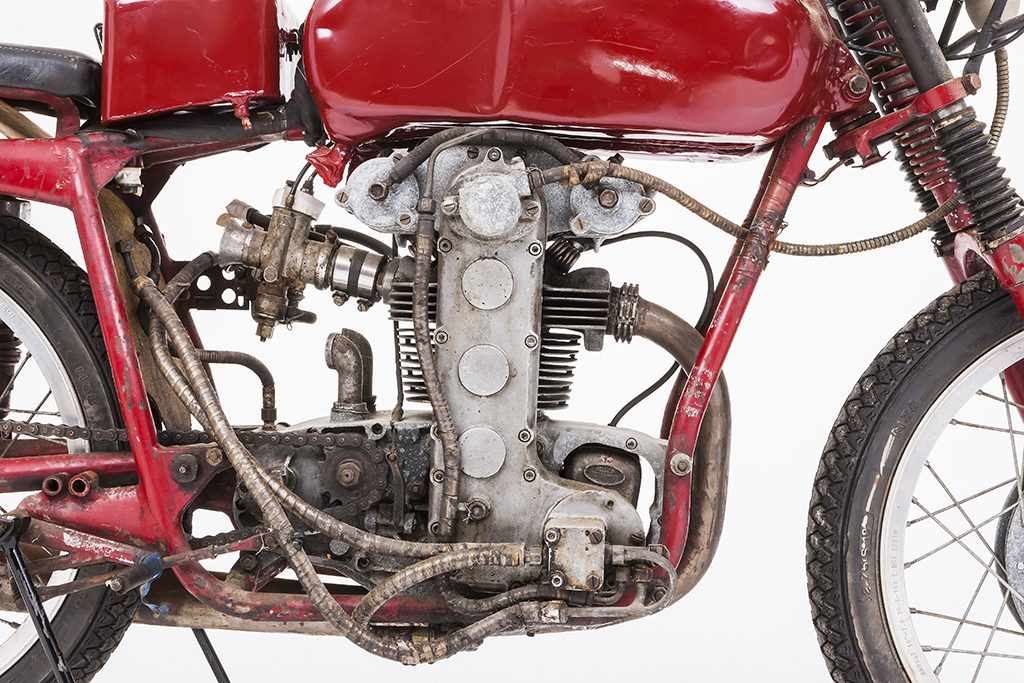

But nothing equalled the struggles they had with the recalcitrant 203. It proved a beast to get started and often shredded its internals when it did get up to speed. “The 203 was crap for reliability,” Neil says. “It had the worst finishing record until we got it fixed but it was 100 per cent from then on.”

Essentially a 175 Bialbero with 5 mm overbore, the 68 x 56 mm MV 203 had common architecture with the 125 but a 15 mm larger piston. The little one would rev to 11,200 rpm and reach a calculated 109 mph while the 203 would do 10,500 rpm until the big-end bearing let go and filled the oilways with silver shards. After the 1957 TT Len used his contacts from BSA days and approached Alpha Bearings in England for a solution. Alpha devised a new bearing assembly with one less row of rollers that allowed a sturdier cage and produced the desired longevity. Terry’s supplied replacement hairpin valve springs. Len had a bunch of slightly used Gold Star valves and Alpha machined them to fit the 203, improving valve life exponentially. The BSA manufacturing empire had access to good metallurgy, while the Italian team mechanics simply discarded valves after every race.

Agusta works mechanics offered no help apart from selling replacement parts, and did nothing to sort the 203’s starting problems. “The works mechanics resented the fact we had the 203, so they wouldn’t tell us how to fix it. The 125s would start in three steps but with the 203 you’d end up having to wait 20 seconds until a pusher was allowed to step in and help,” says Neil. Much later they discovered the idle jet in the Dell’Orto carb was far too lean, but that was not until they were back in Australia. “It started right away after that. You just had to keep the revs above 3,000.”

Though the odd rookie misadventure kept them from earning any world championship points, they lived the young man’s (perhaps overrated) dream life of the mid-’50s Continental Circus as privateer motorcycle racers. Wins eluded them but they achieved many competitive results and ran frequently in the top five at grand prix level. They avoided the tragic consequences that claimed the lives of some of their friends and contemporaries. They finished the 1957 season relatively unscathed and returned to racing in 1958 but much of the glamour was gone. Gilera, Mondial and Moto Guzzi had all retired from the world championships at the end of ’57, citing mounting costs and declining revenue. In 1958, “It felt like the party was over,” Neil says. “It was harder to get starts and money was scarce.”

At the end of the 1958 season Len returned to Australia with the three bikes and Neil went back to Canada, married and started a family. In 1962 they moved for three years to Australia where Neil sold his 125 before they returned to Canada to stay. He had called an end to his motorcycling career when his prospective bride, citing a traumatic experience from her youth, announced that it was the bikes or her. Neil’s training and work experience paid off and he enjoyed a long career in residential property development while they raised a son and daughter.

Len, “a stubborn bugger,” never married but remained in Australia where he operated a motorcycle shop in Warrnambool. He raced the two MVs locally from time to time, once winning both the 125 and 250 cc classes in the Victorian TT at Fishermen’s Bend. He held on to the MVs until his death in 2002, whereupon Neil and his son Ian travelled to Australia to settle Len’s estate and shipped the bikes to Canada. They remained in storage and out of sight in recent years until Neil decided to tell his story and approached local members of the Canadian Vintage Motorcycle Group, who helped him uncrate and assemble the 203 for display at a motorcycle show in Toronto.

After a long and checkered career, the pair of MV Agustas remain together today as living testimony to a vanished era—remarkably still in the hands of their owner from bygone days.