When the streamliner went off the rails, the sound was not what you might have expected from a thousand-horsepower pencil cartwheeling across the salt bed. “It sounded like a couple of soft bangs,” recalls George Cronkite, whom you met in the August issue (First Person). He was down at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah late in August, preparing to ride his 43-year-old Suzuki TS400 Apache (which you also saw in that issue of the magazine) for a land speed record, when he observed the streamliner crashing.

Cronkite was saddling up for his own run at the time. “I didn’t really need to see that,” he says. “I think his engine blew. It went end over end. He was probably doing 200 miles an hour.” Cronkite was “a fair distance away” from it, but he had a clear view. The fast guys use an eight-mile run, he says, which provides a lot of speed-up and a lot of slow-down to sandwich the timed mile. Those fast bikes, he says, are other-worldly. “The rear tire is kicking up salt, so it looks like they’re leaving a vapour trail as they go across the salt.”

Cronkite was not in much danger of crashing, or of making a virtual vapour trail—his speed would be many miles per hour slower than a streamliner’s—but he did manage to establish a record, and to make a joke about his old Suzuki Apache being another World’s Fastest Indian.

“I ended up doing a final return run of 81.5 miles per hour,” he said in an email message sent from his Nanaimo, B.C., home. “Which is pretty good for a 1973 396 cc two-stroke single dirt bike.” Some time after he got home, he had the Suzuki dyno-tested, and got 22.8 horsepower at the rear wheel. It takes a certain amount of crazy guts to ride a thousand-horsepower fairing across the salt at two or three hundred miles an hour, but it takes an appealing kind of chutzpah to ride a motorcycle that makes 23 horsepower on the Bonneville Salt Flats in search of a land speed record.

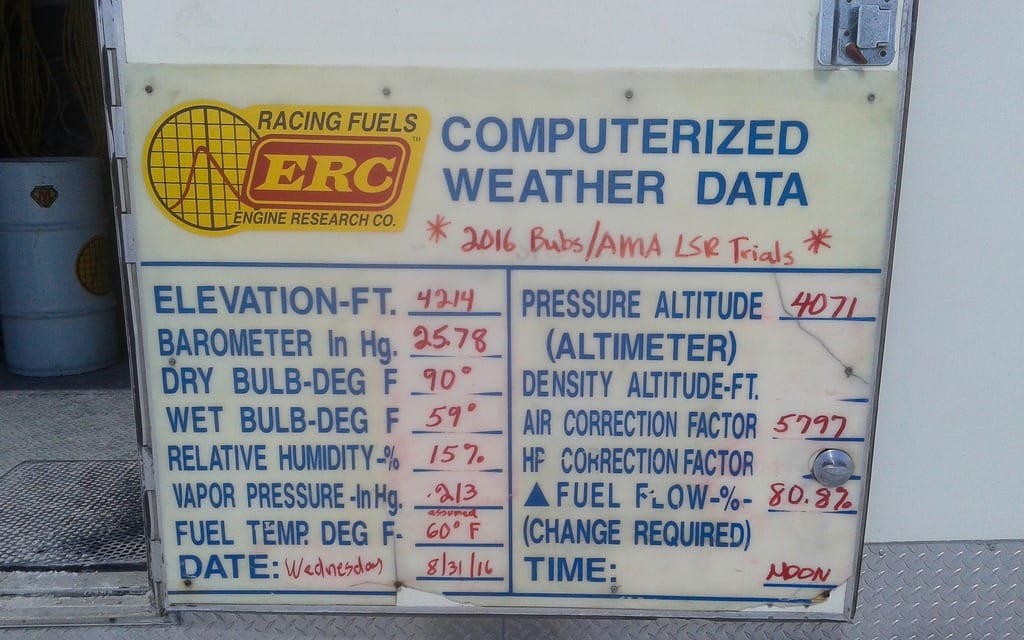

We got him on the phone to talk a little more about his experience down there. The Suzuki was bone stock, with 43-year-old pistons and rings, and he registered it in a brand-new class for old bikes: 500 Production Classic. There wasn’t really such a thing as a practice run, he told us. You just went out, and if you liked your speed on the way out, you tried to do it again on the way back. “You could make as many runs as you wanted.” The course for bikes that were unlikely to do much more than 100 mph was three miles long: one for go, one for show, and one for slow. Over the course of a week, he made many adjustments, playing with the jetting and gearing, which was not a simple matter because the salt flats are 4,200 feet above sea level and the air gets hot under that Utah sun, “at least mid-thirties.”

He swapped his drive chain, experimented with the jets, made a run, tried another jetting change, and then another run. A mile’s run-up was more than the Suzuki could make use of, so he took it easy, built up speed at less than full throttle. “Somebody told me that’s good, you don’t get the engine too hot when you take your time getting up to speed. It depends on the bike, too. But a mile is a long way, especially when you’re running at redline.”

He had a speedometer on the bike, “so I could glance down at it, and I knew I had a good run, so I thought I’d go for the return run. I told them I wanted to do that.” He was out there, “way off at the end of the course” with a couple of other guys who were also waiting to make a return ride. “It was kind of neat,” he says. “It’s a beautiful place.”

It turned out that he had run just a little over 79 mph, which he might have done the week before on the Island Highway aboard his KTM—but at the Bonneville Salt Flats, on his trusty Apache? It must have felt faster. He had never done that kind of thing before, but he felt confident on the salt. Rules called for a steering damper, but the Suzuki had one as a stock item, and the bike ran straight. Riding on salt is different than riding on asphalt, though. “I didn’t have anything to compare it to, and I was surprised how bumpy it was. I was expecting it to be smoother. But it felt really good. I found the bike to be really quite stable. You have to have a steering damper, and my bike came stock with one. So it felt surprisingly good.

“I was hoping for more (speed). Friends told me you can expect to lose twenty percent at Bonneville just because of the altitude and the temperature and the traction. I was hoping for a hundred miles an hour but the reality came to me pretty quickly that that wasn’t going to happen.”

But on the return run, “I could see I’d done a little better.” He parked the bike and went to get his tools. “You have to take your engine apart, and they measure it up.” For some guys, that’s a lot of work, but there’s a sweet advantage in having an old two-stroke single. “In my case, it was just a matter of popping off the head. The head scrutineer measured up the bore, and he said it was good.”

Since he had run in a new class, the sheet was blank, so even though he did not have confirmation of his two-way-averaged speed, Cronkite had the first record in 500 P-PC (still does, at this writing). There was some confusion about the matter, and for a while he didn’t know if it was true, but late in November he finally heard from the AMA that, yes, he was a record holder. But still, no confirmation of his actual speed. It was about 80 mph, anyway—that much he knows.

That’s not what we think about when we think about a land speed record at the Bonneville Salt Flats, of course. But Cronkite didn’t go down there to shake things up. He went because he thought riding that bike on that salt would be fun. “Even the trip down there is fun. You go through five states getting down there, Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Nevada, and into Utah. But Bonneville’s a great experience and it’s very well run. I found the people there so nice and helpful and willing to share their knowledge and expertise. It’s not often that you find a group of such nice people. They were from all over the place but mostly Americans and Canadians. A lot of Canadians.”

He said he spent a lot of time watching other bikes. “I’m just amazed by the engineering that I saw, what people have built. There were a couple of electric bikes—they’re really quiet—and there was a lot of really high end stuff. But also a lot of really genius backyard mechanical construction. It was fascinating. A lot of skill in some of those bikes.”

And then there was the geography of the place. “It’s a beautiful place. Stunning. Sunrises are spectacular, when there isn’t any racing. And when you’ve made a run and you come back to the middle, the thruway. You take your helmet off and sit there for a while. No bikes running, absolutely dead quiet. Not much wind. Being in the middle of a quiet desert, but it’s all white, like the north country with snow.”

Now, Cronkite’s Apache is undergoing reconstruction. He’s rebuilding the top end, and next year, he’ll be back at Bonneville, with a new pipe, a K&N filter. If no one challenges his 500 P-PC record, it’ll stand, because he’ll run in a different class, what with the modifications and all. He wants to break 100 mph. And why not? When you’ve earned a land speed record by hitting 80, there’s only one way to go.