When you can’t double back, you double down

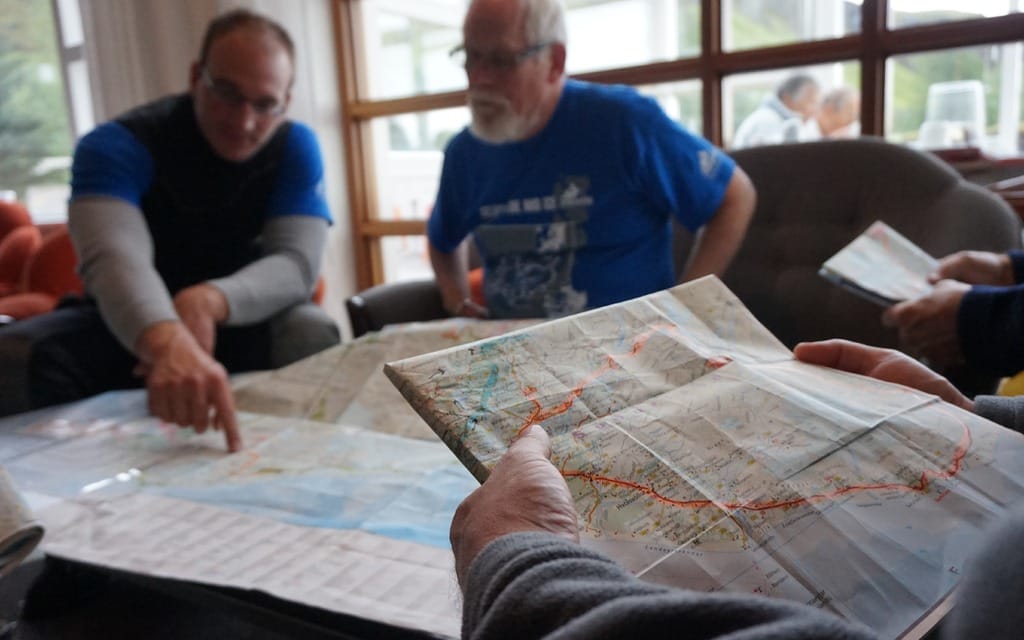

There’s a decision to make. Tour guide Michael Kreuzmeir strides into the hotel lobby resplendent in fluorescent-green riding gear. “So,” he says, “who’s coming to Landmannalaugar?” “I’m game,” I say. For me, today is the culmination of the tour, the fulfillment of my vision of what riding a motorcycle in Iceland is all about: gravel, mountains, rivers and remote beauty. But do the others see it that way?

Fred and Bryna definitely don’t, having already opted for an alternative paved route, bypassing Landmannalaugar by taking the still-scenic Ring Road. The support truck will follow them, as will Jörg, who, judging by what I’ve witnessed, could handle the gravel and water crossings. “I’m sure it’s lovely in there,” he says, tracing a finger along the highland route we’ll be taking, “but I just can’t stand wet boots.”

“I’m in,” says Victor, another competent rider. Vincent, whose elucidations on riding techniques belie his humble abilities, nods in agreement. “I came here for gravel,” he says, folding his arms over his generous midsection. Wayne, in his 60s, has the haggard look of someone who’s been troubled by this decision. “Sure. I’ll give it a go,” he says, his smile smacking of half-heartedness. Michael holds the door as we file outside to the bikes, raising his eyebrows as I pass as if to say, for better or worse here we go.

And for a while, the going is good. We head southwest from Kirkjubaejarklaustur and leave the Ring Road (and the pavement), turning north on the 208, which branches into the F208 just before Búland. Edelweiss riding etiquette says you don’t pass the tour guide (or any tour member, for that matter), but being a journalist has its perks. I pull my Triumph Tiger XCx alongside Michael’s, point at my chest and then gesture down the road. He nods. I smile, twist the throttle, and surge ahead.

It’s not that the pace is egregiously slow — indeed, it pays to take your time and pay attention for potholes on Iceland’s interior gravel roads. The pretext is that I have to set up for photographs of the passing group, although, truthfully, there’s more to it. This environment, a lone gravel road snaking through an undulating, rock-and-moss-strewn landscape with mountains looming on the horizon — inspires my inner explorer. I want to be the first to round that bend, the first to crest that hill, to see that vista. Fanciful thoughts, of course. I’m riding a road that’s seen many treads; I couldn’t possibly be the first.

Still, there’s a sense of excitement, encouraged by the joyous character of the Triumph’s torquey 800 cc triple. Even the weather, which this morning appeared ominous, has taken a positive turn, dark clouds becoming a dull overcast with sunlight occasionally swathing through. I climb a rise and savour the scene, a verdant green valley spread out below, its belly crisscrossed by bright blue streams bathed in dappled light. Except for the wind, there’s silence, then the throaty sound of Tigers approaching.

Jubilance turns to solemnity when we reach the first water crossing. It’s taken over two hours to get here, supporting Michael’s assertion that once committed to this route there’s no turning back; there simply isn’t enough time to retrace our path and take the long way around. There’s a collective intake of breath as we pull up on the near bank. We dismount for a breather while Michael scouts the crossing.

It’s wide, about the width of a good-sized suburban lot. Michael stands up on the pegs and enters the river at a slow, steady pace. The bike sinks to its axles as he angles across the shallowest section, tires bouncing and deflecting off unseen rocks as he threads his way by bigger boulders while feathering the clutch to maintain an even speed. As he reaches the far bank I glance at my fellows, their eyes following our guide with rapt attention. Michael does an about face and dispatches the return crossing with equal ease. “Who’s first?” he says.

“I’ll go,” says Victor. “Take it slow,” Michael says, “and don’t be afraid to put your feet down. Better to have wet feet than a drowned bike. And if you’re losing it, hit the kill switch to avoid drawing water into the engine.” Victor nods, takes a breath, and takes the plunge.

His progress isn’t as poetic, his course more erratic, and he quickly drops from standing to sitting and saves a bobble with a foot dab. Then he gets hung up on a rock mid-river, stalls the bike, and steadies himself with a foot in the water. Before anyone can shout encouragement, he’s restarted the bike, moving forward, and up the far bank. Vincent’s up next, his approach differing in that he enters the water in a seated position. Indelicate clutch and throttle control have the engine screaming (he blames too-thick gloves) and he stalls the bike several times, but still makes it across — albeit with wet feet. I’m next, taking it slow, feeling the crunch of gravel and every deflection of the 21-inch front wheel. I make it. Wayne’s progress looks promising at first, but then he begins to angle dangerously close to a deeper section downstream. He’s panicking, feet flailing to find purchase as he tries to correct his course. When he makes it across I realize I’ve been holding my breath. We all smile, sigh, congratulate each other, and continue.

The scenery grows increasingly dramatic as we delve deeper into the highlands. We’re no longer pottering over hills; we’re scaling mountains. I pause at the highest point of a pass, dismount and scoop up a handful of Iceland’s rough, eerily light volcanic soil — to think, here I hold the eroded remains of red-hot rivers of lava turned to stone. I allow the soil to sift through gloved fingers as I watch the others slowly descend until they appear as insects in the valley below. Michael has reached the next water crossing. I dust off my gloves, remount, and begin a rapid, joyous descent, hook-sliding around switchbacks, the rear tire sending stones skittering on corner exits.

Water crossings come in rapid succession, and the group has (mostly) gained confidence and competence. Victor becomes more adept with each, and though he occasionally puts a foot down to steady himself, he’s quick to take stock and continue. Vincent has found his own system, crawling into trickier crossings with feet extended like outriggers ready to plop down and stabilize at the first sign of slippage.

Wayne, on the other hand, has developed a worrisome habit. It’s one thing to maintain momentum, but quite another to charge forward out of control. (Michael critiques our crossings throughout the day. “Slow down, take your time,” he says.) As morning creeps to afternoon, Wayne’s strength is waning — so much so that at one point Michael wades into a river to help push his bike across. We come upon two picnic tables — an incongruous sight as we’ve seen few signs of humanity — and take a break.

After the respite there are more water crossings. And then it goes south. Michael is yelling, “No! No! No!” as Wayne’s Triumph keels over into the river. “Hit the kill switch!” Michael shouts as he dashes through the knee-high water. Wayne has pinned the throttle in his struggle to keep his balance. The engine wails and then emits a sickening chug, as though quickset cement has gummed up the cylinders. “That didn’t sound good,” Vincent says.

Michael and I help Wayne to his feet and then right the bike and push it from the river. “Did you hit the kill switch before the engine stopped?” Michael asks, though the strained look on his face suggests he already knows the answer. Wayne, who’s rattled, isn’t sure. Michael begins disassembling the bike to get a better look. After removing the seat, some bodywork and the fuel tank to get at the throttle bodies, he has bad news. “They’re full of water,” he says. “This bike is dead.” “What do we do?” Wayne asks forlornly. “We tow it.” Wayne appears ill at the prospect, and before I realize what I’m doing, I’ve volunteered to pilot the dead bike and let him ride mine.

I’m not trying to be selfless — it’s just our best option. Either that, or wait who-knows how many hours for the support truck to arrive. Michael pulls out his cell phone and looks at the screen. “There’s no signal here anyway,” he says. “You’ve been towed before, right?” “Of course,” I say. I lie.

Michael reassembles Wayne’s bike, strings the towrope around the fork, and then affixes the rope to his bike. “Shouldn’t we rig it with a quick-release?” I ask. “I could hold the rope.” Michael points to the huge hill just up the road. “Think you can hold on to the rope up that, and every hill after that? We’d never make it out of here.” “But if I fall it’ll be like your bike suddenly dropped anchor,” I say. “Then don’t fall.”

Michael sends the others ahead with instructions to wait at the first water crossing. Then he eases forward until the towrope is taut. “For God’s sake, don’t put it in gear,” he calls over his shoulder. I double-check that I’m in neutral, and then we’re underway — jerkily until I begin dragging the rear brake to smooth the starts. I keep tension on the rope as we hit the hill. We’ve carried just enough momentum and are continuing steadily up. Yes, I say to myself, we can do this.

But then Michael’s rear tire catches a rut and loses traction. We come to a standstill halfway up. He can’t seem to get going. I dismount and start pushing. We’re moving forward again, but now I’m running uphill in full adventure gear with no way to get back on. By the time we reach the crest of the hill my chest is heaving, my legs heavy with fatigue. “Oh,” Michael says, while studying his bike’s dashboard. “I’m in road mode. No wonder I couldn’t get power to the wheel.” (In road mode traction control regulates power delivery when traction is lost — less than ideal for gravel.) “Looked like a good workout,” he says with a smile.

The descent offers a different challenge, the towed bike doing the braking while tensioning the rope, lest it become tangled in the front wheel. The trailing bike must also tack around corners to maintain momentum while keeping the line taut. It’s a delicate dance made dangerous by potholes, rocks, and ruts. It’s also intimate, involving deliberateness, anticipation, and trust between riders. It’s also exhausting, and I remind myself to keep breathing.

But repetition breeds confidence. Before long I’m relishing the dance. Michael turns around in the saddle as we trundle slowly along a straight section after successfully negotiating another pass, his helmet cocked to the side as if to say, how are you doing? I flash him a thumbs up. Amazingly, the ride is enjoyable — except for the dread that accompanies descents. And though we’ve yet to reach a river crossing, the thought of being towed through water is terrifying. Pushing the bike across is equally unappealing; these rivers are glacier-fed and exceptionally cold. But luck is on our side.

It turns out Wayne had crashed at the final water crossing of the day. We catch up with the group at the turn-in for Landmannalaugar. I’m whooping in my helmet as we pull into the parking lot. Michael shakes his head. “Of course, it had to be the last one!” he says, though a smile accompanies the words. Wayne looks sheepish. I clap him on the shoulder. “We made it,” I say.

And it was worth the tow. Landmannalaugar stretches out before us, a broad valley surrounded by hills and mountains swathed in brown, green, black and white, snatches of blue sky occasionally breaking through to add contrast to the staggering scene. It looks unreal, the tent city at its centre appearing, from a distance, as an apparition. Hikers come by the 4×4 busload to stay for a few days and lose themselves in the spider’s web of area trails, their flimsy tents staked to the bare earth and bolstered with large stones. There’s a natural hot spring to soothe weary muscles and a school bus converted to a tiny general store serving hot drinks and soups. (Debit and credit happily accepted.)

Thirty kilometres of gravel remain — including some of the deepest, loosest sections to date — and then another 90 kilometres of paved roads before we reach the hotel in Fludir. Michael’s rear tire sends forth a rooster tail as we wrestle with another gravel ascent, my rear tire sliding, the front flirting with the limits of traction as I struggle to keep the rope taut. By the time we reach pavement, I’m spent. Michael sets his cruise control to 60 km/h, and in comparison to being towed on gravel, the ride is almost relaxing. Almost.

The drowned bike is loaded into the truck at the hotel. It looks forlorn. So does Wayne. While others shake hands and offer congratulations, his shoulders are slumped, his eyes downcast, his mood withdrawn. “Chin up, Wayne,” I say, “you made it.” “Barely,” he says. He crashed again on the gravel after Landmannalaugar. “I’m wore out,” he says. “Think I bit off more than I could chew.” Surprisingly, he says he’d come back again. “But I’d rent a car.”