An intervention

I throw a leg over the superbike and pull onto Savannah, Georgia’s, Roebling Road Raceway — a favourite of mine. (It’s a regional track with a charming, laid-back atmosphere — what Ontario’s Shannonville Motorsport Park could be were it not a crumbling dump.) I twist the throttle hard, am reminded that riding a superbike requires all of my attention, and spend a 20-minute session engaged in one of the acts I most adore in motorcycling. But I’m never completely at ease.

My unease isn’t because I’m on a twitchy, volatile motorcycle. Honda’s CBR1000RR is, without question, the superbike that fuses a temperate personality with more than enough horsepower. The reason that I limit my time on the 1000 and eventually drift back to the sublime CBR600RR is because the litrebike is without traction control.

A convincing argument could be made that the CBR1000RR doesn’t need traction control. I could make that argument — and a good one — myself. But there is a difference between forming supporting arguments while you’re seated at a keyboard and unleashing 160 horsepower to a slick while you’re seated in the saddle. Most of us could walk a two-by-six plank suspended two feet above the ground across a span of 10 feet. But take that plank, with the same span, and put it between two buildings 10 stories up and few would attempt a crossing. Nothing to do with the act has changed. The only difference is the ramification of getting it wrong.

The speed at which technology permeates our life is increasing exponentially. The lives of hunter-gatherers would have been instantly recognizable to their ancestors — they hunted with the same tools and lived in identical dwellings. But since the Industrial Revolution, technology has entered our lives forcefully, insistently, without concern for our opinion of it. I was shocked this week when I saw a man on a flip phone, and wondered how his service provider allowed him to use an ancient device. It must have been six years old. Motorcyclists can be mistrustful of the technology that has infiltrated our machines, but I don’t believe we’ve anything to fear.

I received an exasperated letter (it began “Maybe I’m too old, but…”) in which a man claimed that the overabundance of technology in the machines we ride has downplayed human control and asserted computer superiority. Specifically, he wrote that the Yamaha R1M and its tour-de-force computer enhancement could elevate mediocre riders in such as way as to make their newfound racetrack prowess meaningless. In other words, having an R1M at your side is like cheating on an exam or fudging your skills to get a job you don’t qualify for.

As a rider, I’m fast enough to get into trouble but not always skilled enough to get out of it. I’ve ridden with world champions, and, earlier this year, with Canadian Superbike champ Jodi Christie. What they can do is astounding; their feel for traction and their understanding of how the motorcycle is responding beneath them are vastly more nuanced than anything my sensibilities can bring to bear. Christie can pick a superbike up off his knee and light up the rear tire to square off a corner. I can do that reasonably well on a flat tracker on dirt in second gear at 50 km/h, but at 150 km/h on pavement? Not going to happen — not without a lot of help.

Technology is simply the tools we make for living. A spear is technology. So are gloves and boots. Is a runner that wears shoes with Kevlar or other synthetic fibres cheating? Is a bicyclist with pneumatic tires unfairly using air to cushion his ride? Technology isn’t a yes-or-no proposition. Twitter is a pain in the ass. I don’t want to read half-formed thoughts tossed off with no more regard than for a banana skin that’s tossed into the bin. Cell phones? I love them. I can work in the garage and claim I’m at my desk should management call. I want technology to serve me. I want to read Cormac McCarthy by incandescent light in a home heated by a furnace while listening to a Jazz Messengers record on an incomprehensibly complex stereo system.

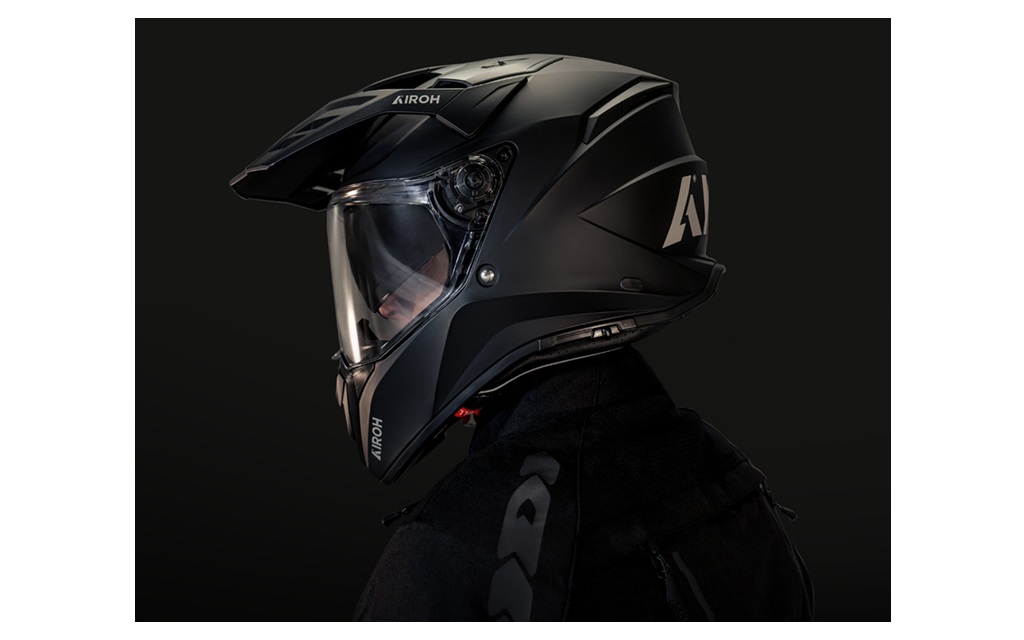

When I rode the R1M it was in the rain. But I didn’t care. I leaned over far enough to grind a footpeg into the track (Pirelli racing rain tires — now there’s a technology) and slithered into corners with the aid of anti-lock brakes. On a decreasing radius left turn I picked up the R1M off my knee and gave it a jolt of throttle and squared off the corner with a spinning rear tire. Not once did I forget that the R1M’s technology was there (had it not been, I’d have tiptoed timidly around the track and had a miserable time), but not once did I sense its intervention. The sheer volume of calculations that the system processed for me to safely make it around the track is mind-boggling (and I’m sure it rolled its eyes once or twice at my indecision) but it allowed me, at 200 km/h, to have the same confidence in braking and cornering that I’d have had at 20 km/h. I was able to skip across that plank 10 stories up knowing that there was a net to catch me should I fall.

If that’s cheating — and maybe it is — I’ve made peace with my transgressions. At day’s end, after riding the R1M, I was exhausted, happy, and tranquil. Sensations that occurred naturally, without the necessity of alcohol or pharmaceuticals to get me there — all it took was a little technology.