It’s the smallest details that cause the greatest headaches.

By Michael Uhlarik

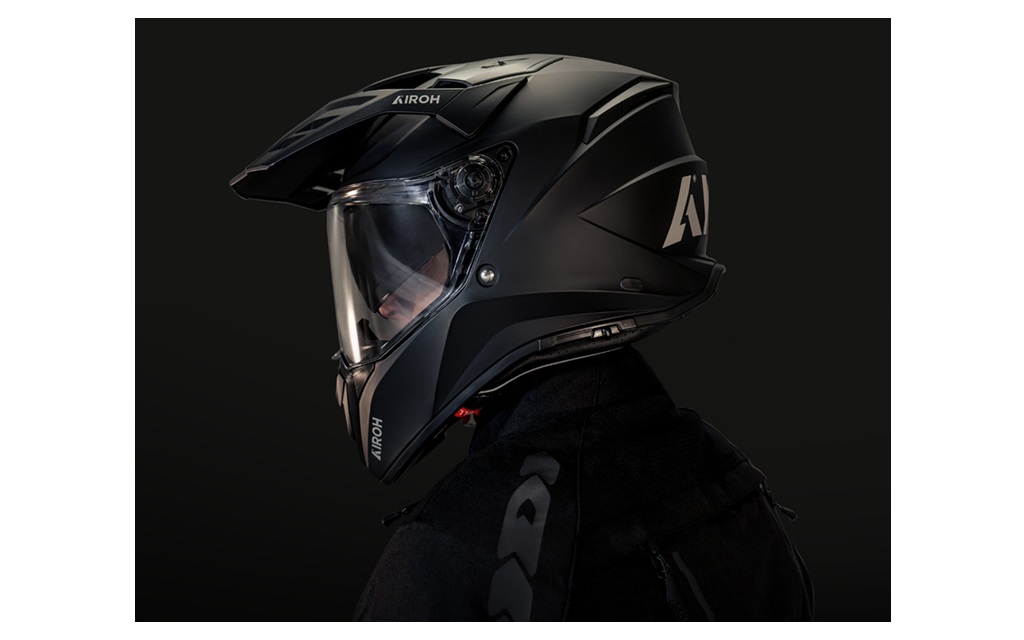

I have a fetish, and a highly visible one: motorcycle headlights. And now, while I work on the design of an electric motorcycle, it’s giving me some genuine excitement.

Today’s only serious street going electric road bikes, the Brammo Empulse and Zero DS-11, both use the same headlamp, one that I designed for the Yamaha MT-03 more than 10 years ago. Manufactured by Italian supplier Triom, that lamp has become the longest-lasting legacy of my work with Yamaha. Since its debut in 2005 on the production MT-03, it was quickly adopted by the European tuning community as the aftermarket headlamp of choice for streetfighter conversions. By 2008, a couple of small Spanish motorcycle manufacturers like Moto Hispania and Metrakit made their own imitations while I quietly wished that I had negotiated a design royalty for it, an impossibility that would have made me fantastically wealthy.

When Brammo unveiled the Empulse R prototype back in 2010 wearing the venerable Triom MT-03 lamp on its prow, I was mildly flattered. I surmised that it was an expedient solution for a small company that was going to, undoubtedly, produce its own design for the production model later on. It was through arched eyebrows that I examined said production model two years later sporting the same part, unchanged. Almost simultaneously, Zero presented the updated DS line which used the same headlamp. Here at last were two all-new made-in-America motorcycles that could boast innovation and showing the courage to enter the unknown and turbulent waters of electric propulsion, but comically wearing the same hat to the party. However disappointing, it highlighted the limitations small manufacturers face.

Face Forward

Vehicle designers know that the face of a motorcycle or car must be original and noteworthy. The expression of a bike when viewed from ahead, like that of a person or animals, must not be strange, and must be instantly identifiable. Humans respond strongly to the perceived character of facial expressions, and this is no less important when regarding objects that contain anthropomorphic qualities. In car design, the fascia (automotive design jargon for the assembled lights, grill and front bumper treatment) is one of the most critical brand elements. Auto headlights, originally just circles, evolved to begin the inward frowning trapezoid that has, since its introduction on the 1974 Citroen CX, become the absolute standard automotive lighting concept.

Motorcycles were decades behind automotive trends. In the 1980s when Japanese brands accelerated motorcycle design beyond the pastiche of European tradition and into the present, headlamps were still afterthoughts in the shape of either a rectangle or a circle. Sportbike designers managed to do something interesting by sculpting the plastic surrounding standard headlamps, such as the sunken twin sockets of the Yamaha FZR 250/400/600, or by placing a transparent cover over them that broke up their shape, like those on late ’80s Suzuki GSX-Rs. The mould was only broken when Yamaha produced the YZF750 with the so-called “cat eye” lenses in 1993. This was one of the first times that a manufacturer designed a headlamp shape and then had a supplier work to realize it. Those tiny corners added to just another pair of parabolic reflector lenses was a breakthrough. From the stories told around GK dynamics, Yamaha’s exclusive design bureau, getting it done was tantamount to pulling teeth from a lion’s maw, such was the resistance from the supplier.

Back in the early ’90s, headlamps were all covered in tempered safety glass, the production and development of which was costly and limiting. The miracle that enabled change was the development of polycarbonate plastic lens covers, following the car industry, something that saved money and weight, and allowed unlimited design potential. Yamaha and Kawasaki were early enthusiasts of this strategy, and with the introduction of compact projector type (or polyellipsoidal) lighting technology, designers were given new freedom. Motorcycles of exception from the Ducati 916 to Yamaha’s R series all owe a good portion of their success to their unique and innovative fascia designs, due exclusively to these new lighting technologies.

Illuminating

It sounds like the simplest component in the world, the headlamp, when compared to the obvious complexity and technical challenges of say, a superbike engine. But in motorcycle development, it is the unlikely little bits that cause the greatest headaches. An engine has precious little regulation forced on its architecture, but the rules and laws governing headlamps are legion. And each legal jurisdiction has its own unique demands, often contradictory and always thoroughly arbitrary, that place enormous limitations on design and functionality. In Europe a motorcycle designer must become intimately familiar with Directive 2009/67/EC 32009L0067 on “two and three wheeled lighting instruments,” a hilarious 120-page tome that gives no quarter on the size, shapes, intensity and location of turn signals and the like. Get this wrong by one millimetre or five lumens, and your company’s product is barred from sale within the European Union and surrounding economic sphere. The United States Department of Transportation is a breeze by comparison, but then they outlaw things such as transparent signal lenses, or signals integrated with headlights. A measure to keep Harley competitive? Not at all. In all likelihood it just hasn’t been challenged in 30 years, and no one has bothered to do so.

For most companies, the simple solution is to pick up the phone and get one of many established lighting manufacturers such as Triom, ECIE, Cibie, Rinder, and Hella to provide a turnkey solution. They know all these barriers and ways to get approval, delivering completed parts or subassemblies that meet or exceed requirements. But having worked with all of the above, I know that design challenges remain. Lead engineers are weary of deviating too much from proven designs that are guaranteed to pass. Designer-engineering meetings inevitably involve horse trading, wherein the styling is compromised here and the technical specification upgraded (and made more expensive) to compensate. It is a messy business that sometimes requires some political hanky-spanky.

The rear brake lamps of the Ducati 916 are a good example. They are EC approved, officially. Unofficially, they fail, but squeak through on of a technicality. While they bear the EC stamp proving that they provide enough visible surface area and lighting intensity, this is only when they are tested as stand-alone parts (which they were). Once installed on the Ducati, their centre section is behind a body colour strip that cuts its total visible area by close to 20%, severely reducing visibility. Italy being Italy, especially 20 years ago, it was business as usual. And a good thing, as the stunning looks of the 916 were preserved.

Design Temples of the Japanese Industrial Juggernaut

In the winter of 2001, inside a poorly heated storage unit outside the Yamaha Motors Italy plant near Monza, the MT-03 headlamp took shape. Despite being the world’s second largest motorcycle OEM, Yamaha then had no proper design studio anywhere in Europe. All of the work was done in 2D (the concept drawing phase) at our offices in Amsterdam, with clay and 3D computer modelling punched out at various locations across France, Italy, and Spain, often in unused corners of factories which were poorly lit, dusty, and most infuriatingly of all, open to general staff. Trying to concentrate for five to eight weeks on the perfection of a clay model is a task made considerably more challenging when random factory personnel barge into your space, lit cigarettes in hand, to proffer unwanted advice and make conversation. Italian staff were difficult in particular, probably because as a culture they are convinced of their innate artistic superiority. Listening to my music via headphones, sculpting tool in one hand and kneading a blob of hot clay in the other, I would be lost in thought about how best to resolve a tank line or panel connection, when suddenly I would become aware of a guy in overalls standing next to the bike, speaking.

“A me piace…” A rambling critique was in progress about bikes the guy liked, why my model was good, and of course suggestions on how it might be better. Ask any professional, no matter what field they operate in, and the universal opinion regarding committee design is pretty consistent. I don’t look over your shoulder, judging, while you work. This may look like a lark, some kind of grown up Play-Doh activity, but it is actually a serious process. GK and Yamaha understood this very well, and gave design tremendous leverage and resources within the structure of the company. But in Europe back then, there just wasn’t enough new product R&D to justify building a dedicated 3D studio. So about once a year we got shuffled around for a couple of months to make do. Good design had to be squeezed out whereever it could be made to happen.

Lighting the way

That said, working for Yamaha was the best professional job I ever had. And when it came to design detailing, I maintain that GK-Yamaha are the best of the pack. At a time when headlamps were still being treated as evolutionary details to be done last or as off-the-shelf items, I was free to experiment. In those days I read Wallpaper magazine a lot, which each month presented a tongue-in-cheek elitist view of the world of furniture, interiors, and lighting. I saw lots of truly great contemporary design detailing in sports gear, automotive interiors and fixtures, and very little in motorcycles. Headlamps were trapezoids on faired bikes, and big circular reflectors on naked bikes. The MV Brutale and Harley-Davidson’s V-Rod were innovators in that they slanted the traditional round bezel and added in a combination projector and reflector for good measure, but that was about it.

I designed the MT-03 headlamp in two days, after establishing that the design language of the entire motorcycle would be straight lines interconnected by perfect radii. The lamp innards were lifted from the ancient TT600 to save money, thus setting the dimensions. I drew a slightly angled pill shape that curved back at the top, and had very thick walls. The idea came to me that it should look like a human skull that had been highly simplified in a Bauhaus style. I had been motorcycle touring in Scotland that summer on an XJR1300 and picked up a sheep’s skull during a picnic lunch on a pasture. Admiring its shape, I bungeed it to the clocks of my Yamaha and brought it home where it glared quietly at me from the corner of my office. I realized only after I finished the design that it had quietly inspired me.

The MT-03 concept bike released in 2003 had LED bulbs in the headlamp—as far as I know a first in the motorcycle industry, but my decision to employ LEDs was really just a footnote to the whole project, since the production lamp would use the reflector from the TT600. I went to my favourite bicycle shop in Amsterdam and bought three Cateye brand LED lights, ripped them open and handed them to our model maker. A month later the prototype was finished and shipped to EICMA in Milan where its blue glow seemed to amuse people.

Production Design is damage control

The MT-03 headlight was easy to design, but very difficult to nurture into real life. Unlike body panels, which make a relatively straightforward transition from sketch to clay model to production tooling, lighting turns into a nightmare of long-distance relationships regarding abstract concepts like surface area, thermal properties, and cost management of components that are many times removed from the motorcycle manufacturer. At one point, some of the MT’s lamp parts were being sub-sub-sub contracted along a line of communication that spanned four countries and three levels of engineering management, all in different languages and with competing time lines.

As the designer, I was only contacted when a Yamaha representative felt that design was being compromised in some way, which was disturbingly often. Another last-minute early-morning flight. Another introduction to a new (to me) engineer. Another hour-long meeting followed by a really good lunch. In the end, the “skin” of the lamp was all I was really trying to preserve.

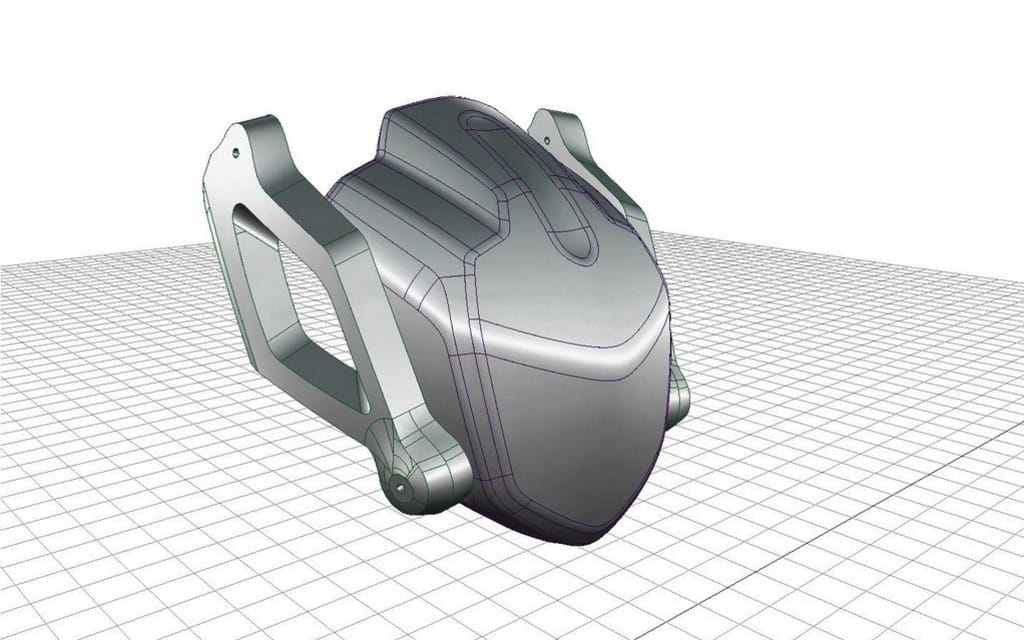

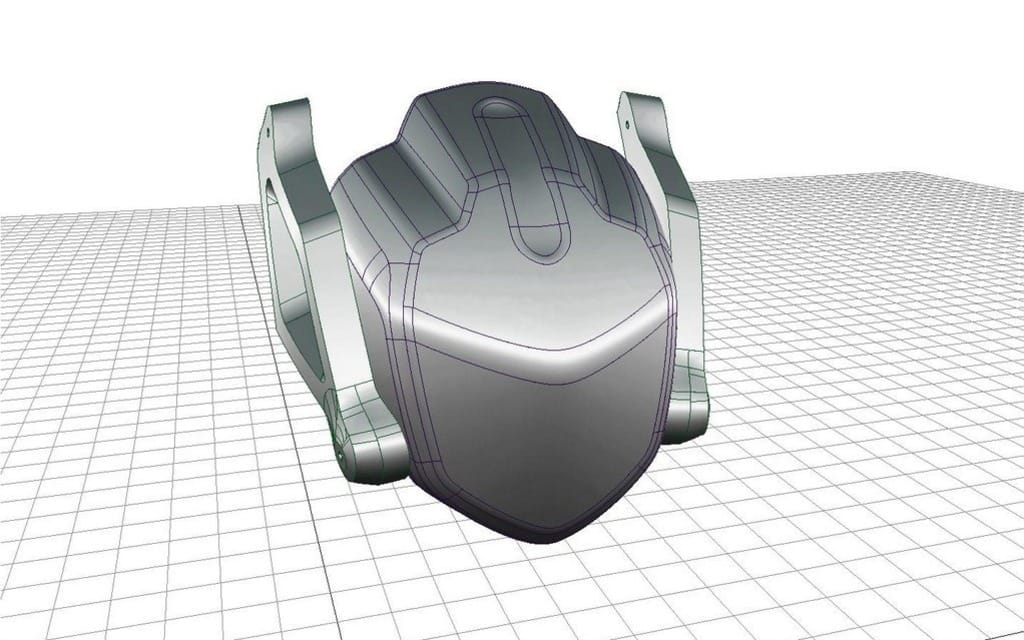

The virtual skin was modelled in Alias, a CAD program invented by a Toronto company many moons ago. Unlike solid models created these days by engineers and many designers in programs like Solidworks or Rhinoceros, what comes out of Alias is not a representation of a three-dimensional object, but a representation of a surface. Yet it is so much more precise and subtle that it’s guaranteed to deliver a brilliant part. Automotive studios all use Alias, or Isemsurf or Catia, for this reason. A young Alias technician named Allesandro and I worked over the clay model in 3D, resolving tiny things, often in ways that seemed counter-intuitive. The long negative scallop on the lens cover that continued up and over the top had been merged with a three-millimetre radius to the rest of the body. However, at the intersection between the front and top surfaces, the radius was doubled, just because when viewed at angles in real life, pure and perfect radii actually look terrible. It was a subtle thing, but it was the kind of optical detailing quality that GK demanded and that I benefited from in terms of professional training. Thanks to the phenomenal talents of Allesandro, the virtual body of the headlamp was resolved to my complete satisfaction after less than a week, and signed off on by Yamaha that Friday, thus etching the design into stone. Triom would now have to bend over to make it happen, and I could move on to other things.

Ode to a Headlamp

Designing motorcycles after I left Yamaha revealed the enormous weakness that smaller OEMs have to contend with when they cannot budget for proprietary lighting. Being forced to shop from a catalogue means designers must be clever about the surrounding bodywork, or mounting hardware to create an interesting and original face. But there simply aren’t many options. Add in the tight R&D deadlines typical of small manufacturers and it can be frustrating in the extreme. Almost every boutique sports bike manufacturer in Italy seems to use the same brake light (an ECIE item), while nearly all mopeds made in southern Europe use the same Rinder-made mushroom turn signals.

I have only been able to design a completely new headlamp once since then, and it didn’t end up being made. Looking at the beauty and intricacy behind the lens of a new Audi, or the Panigale’s LEDs, I must admit to professional envy. I once took great pride in my lighting design, and relished the technical and political challenge of winning over suppliers and engineers with my concepts. That was almost 10 years ago. But the good news is that I am now getting into the nitty gritty of it again for a concept due late this year, and I feel the same nerdy excitement as I used to. Yes, I am amped about designing a headlamp. We all have our motorcycle fetish.