Despite the proliferation of track days, many of you are as terrified about the prospect of riding a racetrack as you are titillated by the idea. We know this because you write us all the time asking if your bike is appropriate, or if you’re too old, or too inexperienced. To inspire you up off the sofa, editor Graham rounded up track day first-timers Steve Thornton and Derreck Roemer for a Pro 6 Cycle event at Mosport. To make it easy for the lads to find their way we put them on Suzuki’s GSX-R750 and Triumph’s Daytona 675R, two of the best track bikes in existence.

TRACK DAY 101

It’s confusing at first, but follow the steps and you’ll be track-bound in no time.

To instigate our track day at Mosport, I went to the venue’s website, which listed its summer schedule. In addition to race events, dates for track days were posted along with the names of businesses hosting them. A Pro 6 Cycle session suited our schedule, and we reg- istered on Pro 6’s website. Costs vary by provider and venue. As Canada’s most famous racetrack, Mosport, at a little over $200 per day per rider, is one of the more expensive tracks to ride.

Most organizers break down riders by skill into three groups. As first-timers you’ll begin in the slow group, but don’t let your ego get in the way; we all start there. If you’re quick you can eventually graduate into the medium or even the fast group.

One of the biggest misconceptions about track days is that you need a race-prepared sportbike to join in. It’s simply not the case. You don’t even need a sportbike, though your machine should be at least mildly sporting. (I wouldn’t hesitate to take a V-Strom or a VFR or a Kawasaki Versys, but I’d draw the line at an Electra Glide.) Machine preparation is straightforward. Your machine must be mechanically sound or it won’t pass tech inspection. Additionally, lights and mirrors and reflectors must be taped up (gaffer tape is fine) to keep the mess to a minimum if you bellyflop midway through a corner. The most significant mechanical change required is the swapping out of your radiator’s antifreeze (owners of air-cooled bikes can skip this part) for a mixture of straight water and a water wetting agent. Antifreeze is slippery and a bugger to clean off pavement after a crash. We took our GSX-R tester to Z1 Cycletech in Toronto, where Chris Pui expertly drained and burped the green slime out of the radiator. You can do this yourself, of course, but a word of caution: don’t forget to put the antifreeze back in for winter, or the plunging mercury could rupture your bike’s internals once the freezing point is breached.

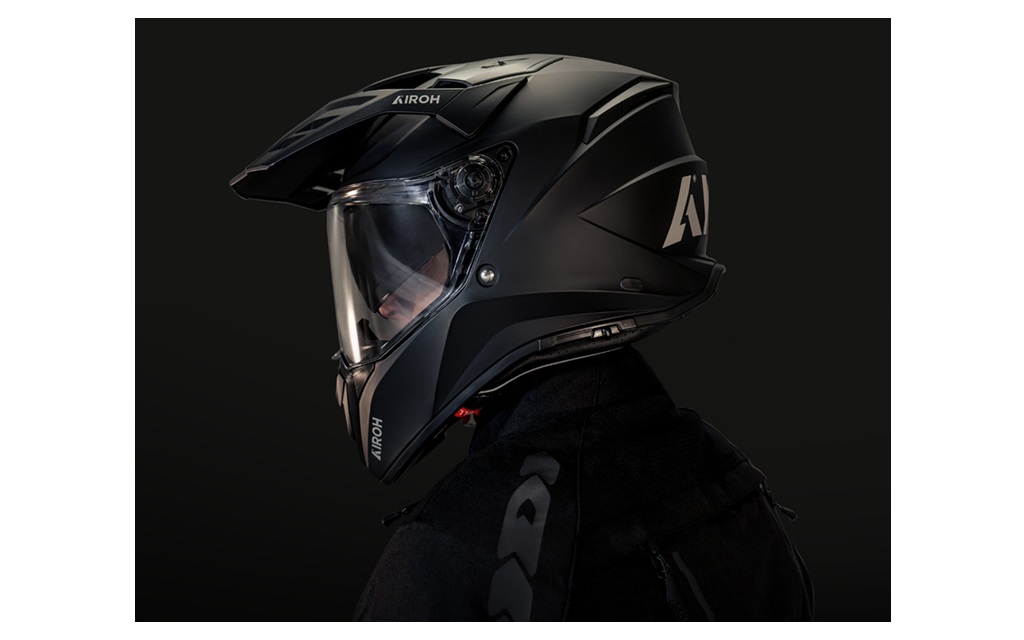

If you’d rather not buy leathers, some track day providers will rent you a set or send you somewhere where you can. You’ll also need boots, a back protector, suitable gloves and a full-face helmet. Most organizers require helmets with Snell certification, so take your time reviewing the organizer’s websites and ask questions until it all makes sense.

When your day arrives get to the track early (you’ll need to register and have your machine inspected) and then suit up in plenty of time. Sessions are typically 20 minutes in length, and though it may not sound like a long time, it is. Beyond that, take it easy, don’t rush yourself, and take pleasure in knowing that you’re doing what many motorcyclists would love to do but haven’t screwed up the nerve to try. Good on ya.

– Neil Graham

Steve Thornton has always wanted to ride Mosport. But he won’t enjoy himself until he can sort the corners out.

“Steve, don’t be nervous about this. It’s just a track day.”

I’m standing in Neil’s office doorway. A moment ago I felt just fine. Time passes. A day or two, and we’re at Mosport. I make my second run and hate it. Nothing is easy.

My plan was simple. I would be slow, and smooth. First, I will not crash. Second, I will aim for the apexes of curves. Third, I will keep my head up and look as far ahead as I can manage.

That’s the plan, but a feeling of profound confusion has come over me. It started with the riders’ meeting, when we were told not to cross a blend line, no matter what, and we were informed that there are two avenues into pit lane, a hot way and a slow way. I don’t know what a blend line is and I have no idea what he’s talking about with the pit lane things. Then we new guys are shown a rough map of the track and told where the apexes of Mosport’s nine turns are, where we should put our front wheel in each corner. I can barely remember how many turns there are and I do not know, at any point in the track, which turn I’m in. It matters because one of them — they call it Moss Corner and I think it’s turn 5 — is a double apex corner. You turn twice in this one. But I don’t know when I’m in turn 5, because I’m not counting. That’s just way too much mental focus for me.

Neil is supposed to come in at the end of the yellow-group ride, hand me the bike he’s on, and let me go out with the greens. Derreck is riding the other bike, and I hope to sit on his tail, watch his lines through the curves, and learn something, because I think maybe Derreck knows something. But Neil is late, and when he gets here, he wants to chat. I get on the bike and head out, but Derreck is long gone. So I’m alone out there. In our first session, a guide towed us around the track, demonstrated the good lines, but I started too far behind him, couldn’t see past the five or six guys in front of me. Now, on my second time out, I’m all alone, and I am drunk with clumsiness.

I do not yet have any idea how fast I can throw this motorcycle into a corner. In what seems like most corners, I cannot see where the pavement goes until I’m at the entrance and steering into it. I don’t know how sharp it will be until I’m at it.

“Steve, you need to hang off the seat, like this.” Neil demonstrates the act of moving the buttocks off the seat. Just half a cheek, he says, as if he’s ordering dessert, concerned about his waistline. And get yourself positioned before you get to the curve, not once you’re in it.

I forget that. I forget to look ahead — entrance, apex, exit; Neil has drummed this into us. “Say it out loud.” I forget to keep my arms loose and my torso tight. I forget to count the corners.

Later in the day, I’m more comfortable, getting used to the track; it’s become familiar, and I know what to expect as I approach each corner. But someone has mentioned holding the throttle open until you get to the bridge, and I try it, but I cannot force myself to hold it wide open, because at the bridge there is a turn, and accelerating under full throttle to the point where you must initiate a turn seems to be placing too much trust in the probability that everything will go according to plan. That the motorcycle will lean far enough and turn hard enough to stay on the track. I know that I could brake smoothly into the corner, that I will hang off the seat and steer the bike into the corner, and I’ve seen that Mosport’s turns are wide and easy, that you could go way outside your chosen line and still remain on asphalt. But I cannot hold the throttle wide open to that point, I just don’t have the mental shit for that. I have another problem, too. Turn 5, Moss Corner. People have talked about it in very specific ways, but I’m not even sure I’m thinking about the same corner. “What about that concrete patch?” I say to Neil. “Do I turn before it? I’ve been turning before I reach it.” “What concrete?” Neil says. Moss Corner is shaped something like a squared-off capital C.

You enter it at the bottom of the letter, make a right turn, shoot up to the top of the letter, make another right turn, and exit at top-right. “If you do it right,” says Neil. “You’ll go right onto the straight.”

I enter at the bottom of the C, shoot to the middle of the C, then make a two-pronged right turn that puts me nowhere near a straightaway. I’m confused. And there’s a huge concrete patch on the outside of the corner. If Neil doesn’t know the concrete’s there, I think, it must not be important, and the next time I hit that corner I let the bike get right up onto the concrete and feel the rear tire slide and the bike shake, and then I’m out of it and onto the straightaway that follows after a left turn.

So let me get this straight: Neil doesn’t know there’s concrete there, and he says if I make the turn correctly, I’ll be launching onto this straight at the exit. I see a huge concrete patch that shakes my bike, and a big left turn before the straight. Someone’s not communicating, or someone’s not seeing something, or this isn’t turn 5.

Last ride of the day, still confused, but getting a little faster. Taking the bike up to some corners under acceleration, hanging a butt cheek off before the turn, keeping the arms loose, looking ahead, saying the mantra to myself. “Entrance, apex, exit.” Still no feeling for turn 5, none at all, and I’ve asked someone else, an old rider like me, guy on a Suzuki SV650. “What concrete?” he said. “I don’t remember any concrete.”

And now I’m out here again. I’m riding by myself, trying to push it, trying to enjoy it because this is my last chance to get it right. Someone passes me; it’s the guy on the SV, and he’s twisting his body to look back at me and tapping his seat. Either I’ve let something come loose, or he wants me to follow. I choose to follow, and he guides me, finally, through turn 5. I see the line, from the bottom of the C to the top of the C, it’s in, turn, go straight, turn, out — simple. And he makes his first turn before his wheels hit the concrete. It all make sense; I had nearly understood it, and now I do understand it — and something else. As you approach the corner, the concrete is right in front of you. The track turns right, but straight ahead of you on the far side of this ribbon of asphalt, like a muddy far bank on a river that turns right, is this concrete patch. I see it and I fear it, but they don’t even know it’s there.

They’re not seeing it because they are seeing the future. They’re looking two seconds ahead of themselves, way to the right, through the corner. The concrete is straight ahead, but the apex and the exit are way to the right, and that’s where they’re looking, and that’s why Neil said,“Say it out loud.”

Entrance, apex, exit. Okay, I get it. Now I’m ready for this track day thing.

–Steve Thornton

Web editor Derreck Roemer is a very fast street rider. That counts for precisely nothing on the race track.

As I mounted the Daytona 675R, Neil gave me a “go get ’em” slap and tickle and said, “Don’t shit your pants out there.”

“No chance of that,” I yelled. “I’ve already gone to the washroom twice in the last half hour.”

I’d done my best to convince myself that I wasn’t nervous, but then a sudden rumbling in my lower intestine forced a last minute dash to the men’s room and told me otherwise. Now it was time to pucker up and ride Mosport for the first time, my very first time on any track.

When I think about it in retrospect, how could I not have been nervous? Our editor, who has rarely given me any kind of riding advice (I’ve become accustomed to Neil throwing me into questionable situations without instruction) had days before begun giving both Steve Thornton and myself track riding tips — edicts really. That alone made me nervous.

Entry, apex, exit was the mantra he’d drilled into our heads, as signposts for where to look when cornering. Keep your arms relaxed, use your legs and core for support, and get a butt cheek off the seat for corners before you arrive at the corner. And smooth, smooth, smooth, for both braking and acceleration. Find your rhythm. Jerky actions upset the bike and down you’ll go.

If that wasn’t enough to think about, there were also the rules and protocols of track-day riding explained to us at the riders’ meeting at the top of the day. Pro 6 Cycle owner and track-day organizer Sandy Noce went over a lot of things but the thing that stuck out for me was the blend line. Neil, too, had told me about the blend line. The blend line is a very serious thing. It is the painted line that defines the entry and exit lanes of the track. Crossing either one — entering the track too early or exiting too late — we were sternly warned, would mean immediate expulsion from the track for the rest of the day. I thought of reigning World Superbike champ Max Biaggi crossing a blend line at Monza last May and being penalized, but at least he wasn’t black flagged and sent home.

Then there were the flags. Apparently, we were told, there’d been some rider confusion about the flags the previous day, so the head track marshal effected his best drill-sergeant attitude and barked out the meaning of each flag and what we were to do if we saw it displayed. We were also told to make note of where the marshal stations were along the track during our warm-up lap. How was I supposed to remember all this stuff? I didn’t even know which way the corners went.

Noce then held a first-timers-only meeting in front of a track map taped to the side of his trailer. He gave us a general briefing on how to ride the track and encouraged neophytes like myself not to go any faster than highway speeds until we had comfortably learned the lay of the land. “You’ll probably not get it out of fourth gear today and there’s nothing wrong with that,” he said. “You’ll be able to go plenty fast in fourth. And you may not get a knee down — nothing wrong with that, either. Take your time to learn the track and work on finding the best lines.” Neil had been telling Steve and me the same thing, but coming from Sandy the advice somehow had greater resonance.

Noce then explained the blend line once again and discussed the best lines for the trickier parts of the course, marking them on the map. Just as my head was about to explode from all the information, he asked if any of us wanted a coach to lead us around for our first session. My hand shot up, as did those of most of the rest of the guys in our rookie group.

Lined up two abreast in pit lane, we were waiting for our coach to arrive to show us around the course. A guy wearing an orange vest rode by and the pit marshal motioned for us to follow. I raised the Triumph’s sidestand, pushed the starter button, and nothing happened. I checked the kill switch, pushed the starter again, and still nothing. The guy in the vest was long gone and the rest of our group was swerving around me. Sweat was streaming from every single pore on my body. Finally I looked at the ignition key, turned it on, punched the starter, and rode off — not the least bit nervous, not at all.

As I emerged from pit lane, the blend line, the thing I’d become obsessively concerned about, appeared to my left. As soon as it ended, I entered the track. Nothing to it. Our guide led us around the track at well below highway speeds for much of the session, only ramping it up slightly near the end. After about four laps I started champing at the bit to go faster (as I often do when riding in a group) but reminded myself to relax and focus on learning the fundamentals.

Back at the CC van, my inaugural session over, I was able to relax and let this new experience soak in, and later, after a few sessions without a guide, I began to fully realize how hard this all was. I didn’t think it would be easy, but as a fast (some would say too fast) street rider I was surprised by how much precision was required to ride well on the track. I had a good idea of what I should be doing, but putting theory into practice was another thing. Just running a consistently decent line around the track in fourth gear was a huge challenge. I was shifting my weight too late, turning in too early, then too late, braking and accelerating roughly, no smoothness, no rhythm. By lunch my right forearm was sore. “Arm pump,” said Neil. “You’re not keeping your arms relaxed. Use your legs more. Squeeze the tank with your knees.”

Whether or not my form improved after lunch was hard to say, but as the day wore on I felt more comfortable and my speeds increased accordingly, to well beyond highway norms. I eventually saw 220 km/h on the back straightaway. Sandy was right. You can go plenty fast in fourth gear.

Mid-afternoon I hit the wall, not the track wall, fortunately, but the wall of fatigue. At the end of the session I pulled up to the van, physically and mentally spent, and had to think long and hard about what to do next. Finally the necessary circuits in my brain connected and told me to turn off the ignition, lower the sidestand, and get off the bike. I thought of Max Biaggi again. How the hell does he do it? I was spent after 10 plodding laps, but he rides for 40 minutes at a time twice a day at warp speed. And he’s 40 years old — younger than me, admittedly, but not by that much.

My exhausted brain had a new and profound respect for the incredible level of skill and stamina that it takes to ride a motorcycle quickly around a track. I don’t think it’s something that a motorcyclist can truly appreciate until they’ve tried it. And I’m counting the days until I can do it again.

–Derreck Roemer

FROM THE SADDLE: Suzuki GSX-R750 vs. Triumph Daytona 675R

The Triumph Daytona 675R is about half an inch higher than the Suzuki in that most important of dimensions, seat height. I sit on it, and my toes touch the ground on each side of it, so it’s not a big problem, but the Suzuki GSX-R750 allows my feet to be just that much more in touch with the ground when i’m not moving, and this is what makes me feel more comfortable on the Suzuki.

It’s true that the Daytona is more hard-edged, but this is a sportbike, not a couch.

When i sit on the Suzuki, I feel like I’m on a larger, lower, longer motorcycle; it’s very Japanese: well made, stuffed full of quality control, as predictable as the numbers on a calendar. It sounds great; snap the throttle open and you get a spine-tingling snarl. the powerband goes from here to way over there; open the throttle at low engine speeds and you’re launching down that track.

The Daytona’s suspension is almost jolting, its clutch lever hurts my hand and the engagement point is almost all the way out. The front brake is too powerful and too quick. The engine’s sonic character lacks the thrilling timbre of the Suzuki. The engine is not as powerful and the acceleration is a little softer.

But this is a track bike; only a nut would buy one of these for the street. And track-days are for challenging yourself. The Triumph may be harder to ride quickly, but if I wanted easy, I wouldn’t be here. The triumph is hard-edged, but seems to focus me more intently on what i’m doing. Call me a masochist, but i’ll go with England on this one.

–Steve Thornton

Having just ridden the GSX-R750 for the first time, in only my second ever track session, I was anxious to go back out on the Daytona 675R — the bike I’d ridden in my first ever track session. I wanted to see if my greater comfort level in the second, Suzuki-mounted session was because of my fast developing skill-set or because of the bike itself. Sadly, it was all due to the GSX-R. The GSX-R is the easier bike to ride, plain and simple: smoother in every way, easier to steer, and on top of it all, faster in a straight line.

That’s not to say that there’s anything at all wrong with the Triumph. The triple, with its top-of-the-line Ohlins suspension, killer brakes, and speed shifter is a fabulous specimen. But it’s harder-edged and less accommodating than the Suzuki, and demanded a heavier hand to guide it around the corners and a more delicate touch on the throttle and brakes. And the 675R’s speed shifter was perhaps too much kit for me. I only really began to use it late in the day, while coming out of Moss corner and accelerating up Mosport’s back straight, and even though the shift light was illuminated, the speed shifter would disconcertingly jerk the bike forward at anything less than savage rates of acceleration.

Admittedly, I began to feel more comfortable on the Triumph as the day wore on and I clocked more laps aboard it, but the Suzuki inspires confidence as soon as you throw a leg over it. And confidence, no matter what your skill level, is the greatest of companions when you’re heeled over in a turn on a motorcycle.

–Derreck Roemer