The author of this article and winner of the 2001 Governor-General’s Award for Poetry, George Elliott Clarke, teaches English at the University of Toronto. He is writing a novel based on Bill Clarke’s 1959 diary. George’s latest book is Red (Gaspereau Press), a poetry collection.

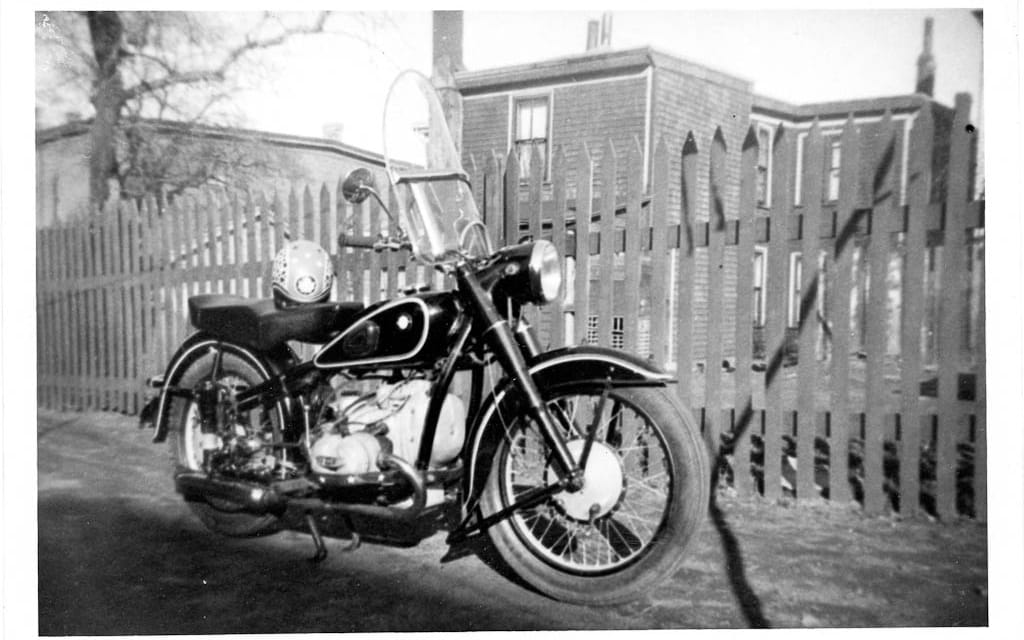

I now own my late father’s black motorcycle helmet, with its red-gold-white-brown-silver flames licking back from the face. I know that he — Bill Clarke — was proud of that paint job, for he says so in his 1959 diary, the only thing of his that I officially inherited upon his death, aged 70, on August 31, 2005, in his native Halifax.

My two brothers and I had always known about our father’s pre-marital, motorcycle days. When he took us for Sunday drives, he’d sometimes jet up a hill and swoop down over the crest to give us that split-second sensation of floating. He also liked to make the 20-minute drive from downtown Halifax out to Sunnyside, Bedford, where we could chow down on burgers and shakes, fries and pop, at the same joints — such as The Chickenburger — that he used to frequent with “chicks” and brother bikers.

When our bicycles needed parts, he took us over to Calhoun’s at Cunard and Agricola, not far from where we lived (first on Cunard, and then on Maynard). I remember distinctly the smells of grease and oil among the motorcycles that George and Doug Calhoun were still selling and servicing in the early 1970s. (We also patronized Jack Nauss’s bicycle shop, perhaps because he was also a former motorcycle pal of our father’s, though his shop was slightly further away than Calhoun’s.)

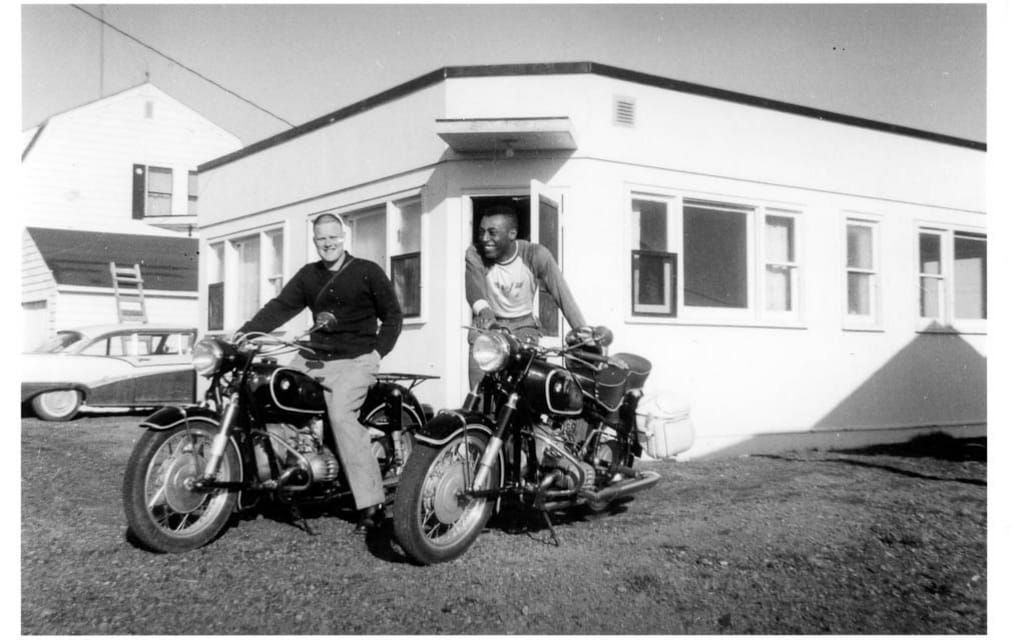

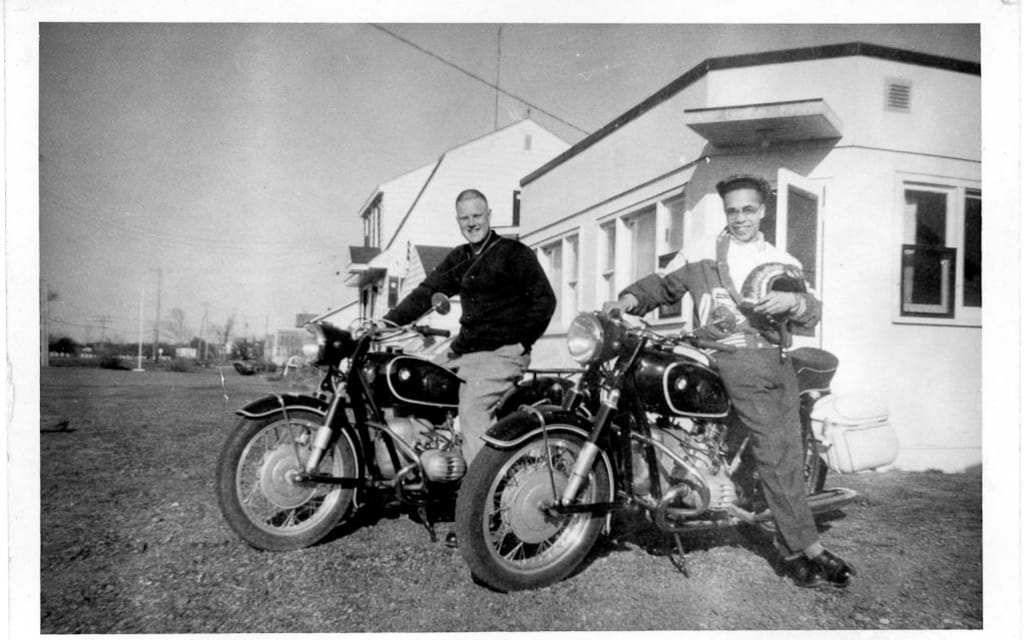

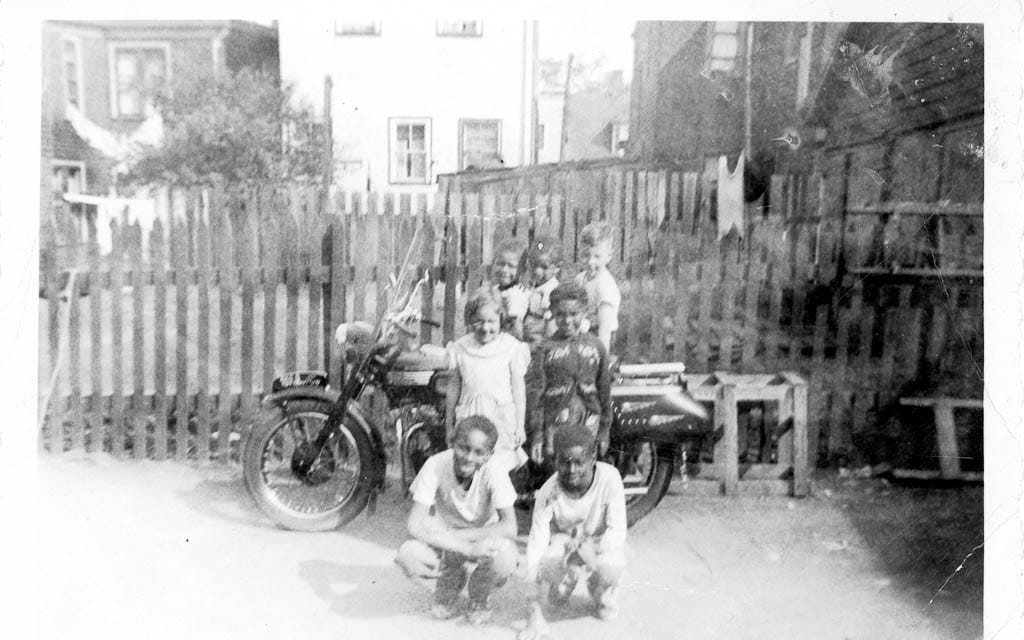

In our home, there was a photo album full of black and white snaps of dark-coloured and brightly chromed bikes, as well as pics of black and white men, posing in pastures, on streets, near race tracks, sometimes with ladies, sometimes solo. They looked romantic, heroic, suave, and chic — these slick men and their sleek machines.

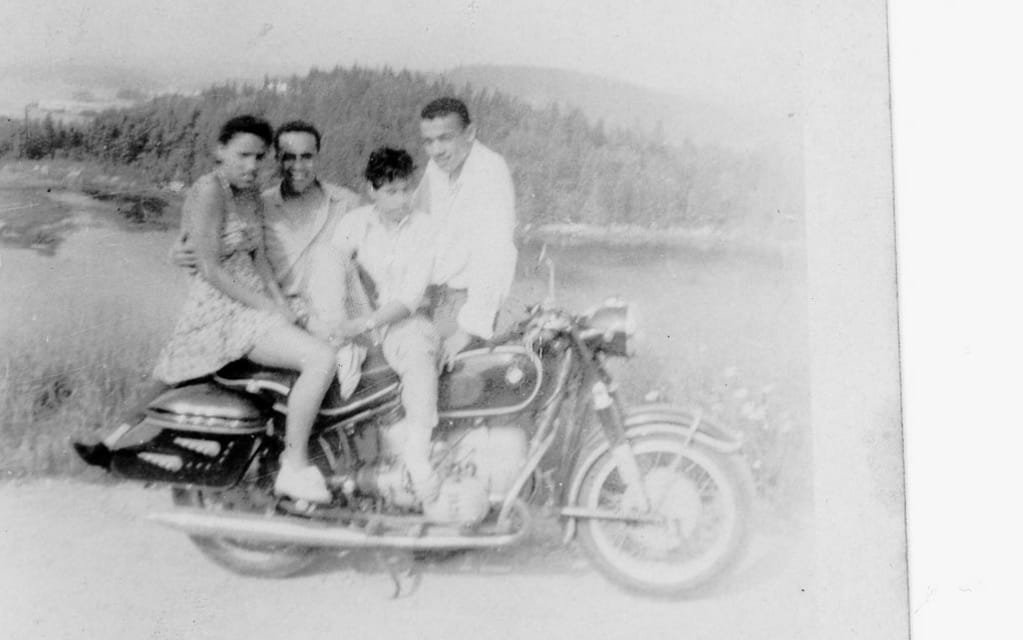

We also saw shots of our parents on their honeymoon motorcycle jaunt through Prince Edward Island in June 1960. Mom wore a bandana; Dad looked proud. Despite the scattered evidence of his motorcycle youth that was bric-a-brac in our home, our father said little about it. Nor did he talk about what it was to be a “coloured” motorcyclist in the 1950s, in the Maritimes. That omission was strange because it’s unusual, even now, to see African Canadians on motorcycles, especially as an only-vehicle-of-choice, and it was even more peculiar five or six decades back. For prudent reasons of economy and climate, it would make sense that penny-counting folks would prefer cars, new or used, to motorcycles, which are limited in what and who they can carry, and which offer no protection from inclement elements.

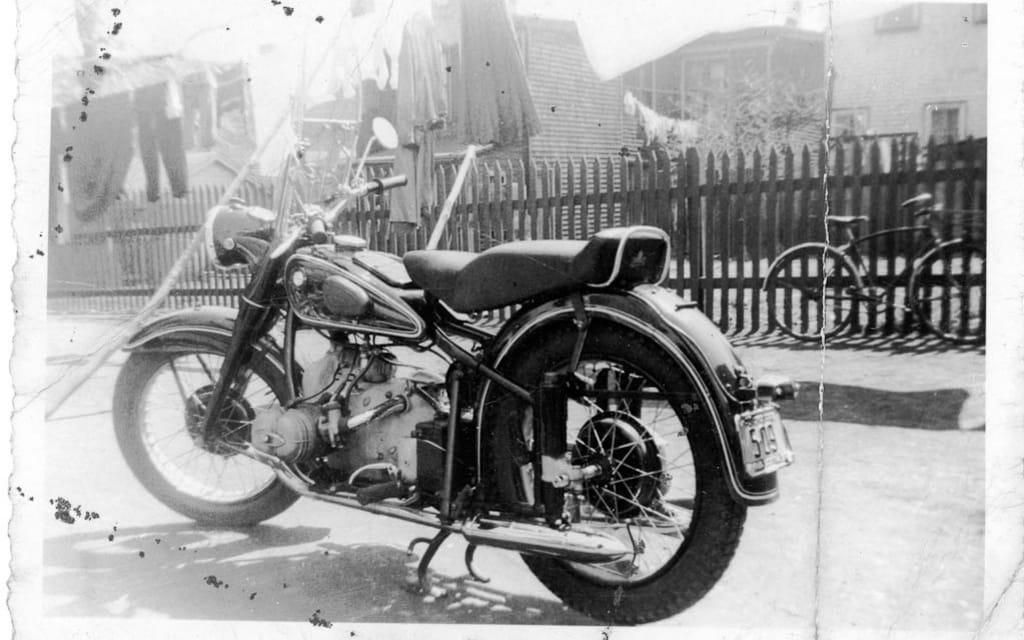

To many black workers, in the days of casual segregation, when jobs were generally low-status and yielded little pay, the motorcycle would seem a luxury, a leisure vehicle, inconvenient for everyday life. Yet, not only did Bill Clarke — always working-class or self-employed — ignore prudence, he bought, remembers one friend, Gordon Hamlin, the first absolutely brand-new BMW motorcycle in Nova Scotia (even Calhoun, the dealer, had been riding a used model).

I’m not sure what year that was, but, by 1959, he was riding a machine, painted purple, that he called “Liz II,” presumably as a jocular tribute to the Queen. He might even have intended a touch of sassy, sexual fantasy in his monarchical nomenclature. When the Queen visited Halifax in July 1959, my father rode his bike to the Garrison Grounds, praying that, in the vast crowds out to greet her and Prince Philip, Her Majesty would notice him, dapper on his spiffy, gleaming BMW.

Like many black men of his era, Bill Clarke worked for the railway, but he was not a sleeping-car porter. Instead, he had the task of carting luggage and linen, to and from the trains pulling into and out of Halifax station. So why did he and one or two of his own brothers decide to invest, literally, in motorcycling? Well, first, the motorcycle offered relatively inexpensive transportation. Too, back then, motorcyclists gravitated toward each other, and Bill Clarke was instantly a member of the Halifax Motorcycle Club, formed in 1955. Race didn’t matter as much as racing; there was a sense of camaraderie.

Maybe as important as any other consideration was the sense that the motorcycle gave Bill and his brothers a sense of liberty as well as status. They were no longer just humdrum proletarians, bossed around by railway managers and sometimes disrespected by passengers. Instead, they became classily cinematic — mysterious men on glistening devices — able to vroom “chicks” about town or whisk them on day-trips to places they’d likely never see otherwise.

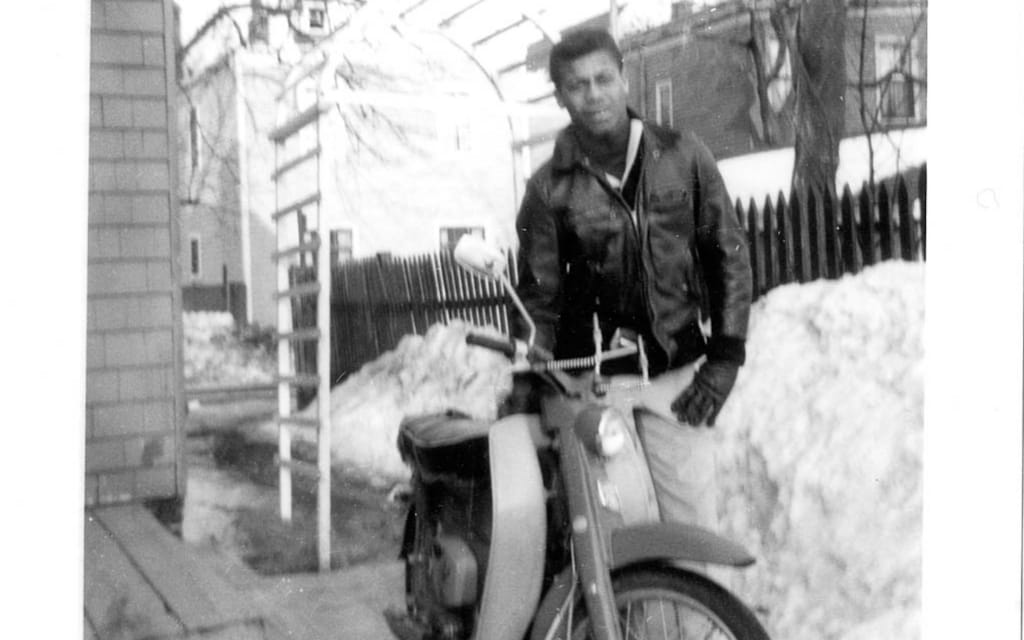

No wonder then that my father’s 1959 diary is so full of yearning — all winter long and halfway into spring — for the day when he can finally get his bike out onto the hilly streets of Halifax. Finally, that day — Saturday, May 9 — arrives, and he decks himself out in his riding leathers, checks himself in a mirror, before he strides down to Calhoun’s to retrieve “Liz II” and set forth on his summer adventures and romances. In his diary, he recalls that the day was excellent cycle weather.

Given his knowledge of World War II (an event he lived through), he probably saw May 9 as being as significant as May 8 — V.E. Day —1945. His sense of liberation is akin to that of Europeans freed from the threat and tyranny of Hitler and Nazism.

True, his fate was not so desperate. Yet there is pure joy in his ability to determine his destination and his speed, to pass other vehicles, to feel the wind around his face, to toot at gals that he can uplift from pedestrian status, if only temporarily, whose pulses he can supercharge while they hug his torso tightly.

Later that same month, Bill turned 24, and his dating became more frenetic, even as he had his eye set on a particular, potential spouse. To be honest, one of the freedoms that the motorcycle awarded him was the opportunity to perfect the Playboy “philosophy”— even within his limited means. His dollars might have been minimal, but the BMW maximized the reach of his charm.

Indeed, the machine permitted him stealth and flexibility. He could woo one lady out of earshot and eyesight of her rival. He could then date the rival, the same day, in a different location. Neither had to know necessarily about the other — at least not until a decision, a choice — heartbreaking for someone — had to be made.

Or, if the situation became tense, it was easy to leap up, kick-start the engine, and vamoose into sunset — or sunrise.

But I also think that the motorcycle appealed to my father for an even more profound reason: it was the machine that projected his bohemian aura and proclivities. He was atypical, and the big, purple BMW helped him to say so. Yes, he was a humble railway worker. But he bought classical music and Broadway tunes and exotic LPs religiously — every week; he did charcoal pencil and watercolour and oil paintings of his buddies and beauties, “guys and dolls”; and he read constantly and widely.

His shelves contained the library — essential for a 1950s gent — of Ian Fleming’s James Bond. But there was also James Baldwin, the gay African- American novelist. There were also works by Norman Mailer and Jack Kennedy (still just a senator, but definitely a man to watch).

In music, there was Nat King Cole crooning Spanish tunes, plus Johnny Mathis adducing the seductive vocals that could help to make an evening with a lady memorable, plus Yma Sumac’s unique, Inca voice that manages to fall throatily between trilling and barking, songbird and barmaid.

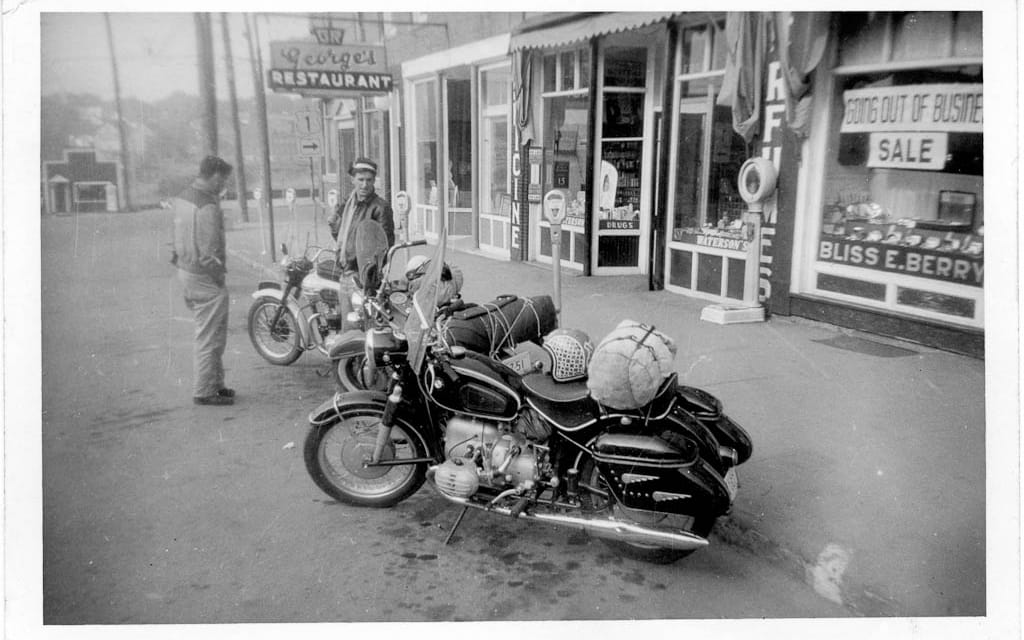

When he motorcycled to New York City, in the summer of 1959, he visited a BMW showroom, yes, but also sauntered around Broadway, even seeing Ricardo Montalban and Lena Horne in Jamaica! He went to the Apollo Theatre in Harlem and witnessed a rhythm and blues review, but he also attended the Apollo Theatre on 42nd street, a cinema that specialized in screening European films about sex — flicks that could not possibly have been shown in Halifax at the time, at least not legally.

Although he only had Grade 10, and left high school at age 18 (meaning that he missed a couple of years along the way), Bill Clarke was a bit of an autodidact intellectual. Aware of world affairs, current art, cinema, and literature, and his own eclectic musical choices, he became a kind of honorary beatnik — at least by black Haligonian standards. Certainly, most of his peers would have known James Brown, but not necessarily James Baldwin, or would have preferred Chuck Berry’s “Roll Over, Beethoven” to Ludwig von Beethoven’s compositions.

So the bike was a means of expanding his horizons — not only geographically, but educationally. He could jaunt to larger centres — Montreal, New York, Boston, and Washington, D.C. — and return with a smattering of French, trinkets from Macy’s, and first-hand knowledge of still- segregated hotels where two dollars would buy you a pillow and a woman to accompany it.

He could ride from Laconia, New Hampshire, up to Montreal through Plattsburgh. In New Brunswick, everyone passing south to get to Maine would stop at a big campsite outside of Saint John. There was the fragrance of apple blossoms, the whiffs of salt-sea-air and fog, the smell of manure on country fields, the aroma of pavement after rain. All of these were, really, the perfumes of liberty.

His travels made Bill a provincial cosmopolitan. The bike transported him from narrow-minded locales to places of wide-open adventure, excitement, and invention. In the summer of 1959, in a New York YMCA, Bill met a Chinese student from Hong Kong, and they spent hours discussing geopolitics, much to their mutual pleasure and enlightenment.

Similarly, he was befriended by an African-American mailman, and then by three white bikers who made him their “leader” on the jaunt from New York City to Laconia. On the other hand, a Manhattan policeman gave him a ticket for going the wrong way on a one-way street. Motorcycling was definitely a college on wheels.

So, the purple BMW was one more way for him to stand out from the crowd. It was his way of being a rebel without actually breaking any heads or breaking any laws. It was a way to be bohemian without having to be bourgeois — or have friends with bankrolls — first.

Indeed, while desegregation of Nova Scotian schools happened quietly in 1954, actual campaigns for racial justice and economic integration came about only in the 1960s and 1970s. Arguably, the very visible biking of black men like my father, in a small, mainly Caucasian-dominated city like Halifax, was a symbol of instant — if ephemeral — integration of “white” space.

Moreover, given that he was ecumenical in his interest in women, the motorcycle could be as attractive to white girls as it was to the coloured variety. Ditto for the motorcyclist himself, a mahogany-tint dude, in black leather duds, straddling a steed of violet and silver.

African Americans could march for civil rights, but Bill Clarke believed that he could introduce eloquent, elegant “Negro” sensibility to the highways and byways of the Maritimes and New England, just by materializing — on his device — in those parts, catching eyes and turning heads. He would be Sidney Poitier playing Marlon Brando.

He would be a non-comformist, yes, but with excellent diction and an immaculate vehicle. One way to demand — and receive — equal service and respect was simply to be polished in speech, dapper in appearance, and debonair in style — even if, in Maine, he sometimes had to camp out under the pines and shave in cold water the next morning. (At Laconia, in the summer of 1959, my father records the note that a news photographer snapped several photos of him in his shades, looking, presumably, quite hip.)

If he had a motorcycle hero, it was likely one from the British Empire, namely, T.E. Lawrence, a.k.a. Lawrence of Arabia. I think he would have preferred the dashing image of Lawrence to the beer-belly, brawling biker image that emerges from Yankee populism. (Canada is always more elitist than America, even in popular culture.)

Later on, he read Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, but I don’t think that philosophical novel captured much of the zest and vigour that my father felt when he was hurtling down roads. But, in 1960, he sold his bike and bought a pick-up truck (with which to do odd jobs). The reason? He had married my mother, and so now needed to be “responsible.” When he put away the bike he also gave up his youthful dreams.

But that helmet that he painted so colourfully and wore so proudly was placed front and centre in every living room that my father later inhabited. It now has a prominent place in my own. When my sister unveiled the headstone that she had had made for our father’s grave, it boasted an etching of a railway caboose. I knew that it was wrong. It should have been a motorcycle, his beloved BMW.